I recently visited the OCADU (Toronto’s fine arts university) graduate exhibition, browsing works by up-and-coming artists, and I noticed an eerie trend. Every time I came across a piece from an ostensibly Asian name, there was a better than 50/50 chance that the piece had something to do with the artist’s struggle with their Asian identity. I thought I was seeing double (triple, quadruple) at first, but no, I had waded through a sea of art pieces of repetitive, identical concepts.

And after a while, I thought to myself, well maybe that’s not so surprising? Fine art is a vessel for self-expression, and living in a city as a minority (Toronto’s extreme diversity doesn’t shield it from liberal racism or regular ol’ racism), you’re bound to come across jarring experiences that make you want to communicate about the adversity you face.

But I also noticed that the source of adversity these Asian art students chose to implicate were not external trespasses, but entirely internal. It was always a painting about their challenges dealing with feeling ugly growing up, or a sculpture about not wanting to move back home to Hong Kong, or an installation about oppressive immigrant parents. One piece was literally titled “Family VS Myself”.

Each of these projects on display were Bachelor of Fine Arts thesis pieces. Imagine you are tasked with putting forth all the creative talent you’ve cultivated and refined over a 4 year academic career, to be displayed for thousands of visitors (and potential buyers) from the community to see, and your first and final inclination is to use it to shit on your parents. Now imagine this theme being repeated by seemingly every other Asian artist emerging from a reputable fine arts university, each one being awarded a degree for it.

This is the state of Asian American rebellion. Asian Americans don’t get very many opportunities in this world to express ourselves, and when we do, we choose to make it very much so about ourselves. We use the rare access to a platform to push back against what we believe (or have been made to believe) is wrong with us, our families, our cultures. We revolt against ourselves by creating these narratives of pain. Our self-expression is only ever a celebration if it’s about “escaping” the imagined limitations of our ethnicity and ethic-ness. It brings a literal and shallow meaning to the concept of “counter-culture”, normally a staple innovation of the artistic world, here a form of wasteful, regressive navel-gazing when it is repeated ad nauseam. Where’s the creativity?

…a form of wasteful, regressive navel-gazing when it is repeated ad nauseam. Where’s the creativity?

Anyone who follows the creative output of Asian Americans can see that this trend of tearing ourselves down goes beyond just fine arts, and into writing, film making, comedy, etc. There’s an argument here that white publishers, editors and curators cherry pick these pain narratives as what Asian American creatives are permitted to present, and I both buy and question that argument. These trope-y stories of struggle we’ve heard over and over again… Are they all we’re allowed to say, or are they the only thing we’re capable of saying? Are we so obsessed with the idea of assimilation into America that we’re incapable of imagining literally anything else? Many Asian American creatives permit this desire for acceptance to castrate our creativity.

And perhaps that is part of the challenge. Asian Americans have very real experiences struggling with immigrant parents and outsider cultures, and those stories shouldn’t be discounted. But at the same time we’re highly incentivized to tell our stories to a white audience due to economic pressures (let’s be real, the artistic patrons and influencers are often white) and, more insidiously, social pressures (the desire to fit in supersedes most forms of filial piety or cultural allegiance). We dissent against ourselves because it’s lucrative. There’s no social or monetary capital behind what we really should be doing with these stories — sharing them within the community as a way to bond with other Asian Americans, an act that would uplift our confidence rather than tear it down.

Many Asian American creatives permit this desire for acceptance to castrate our creativity.

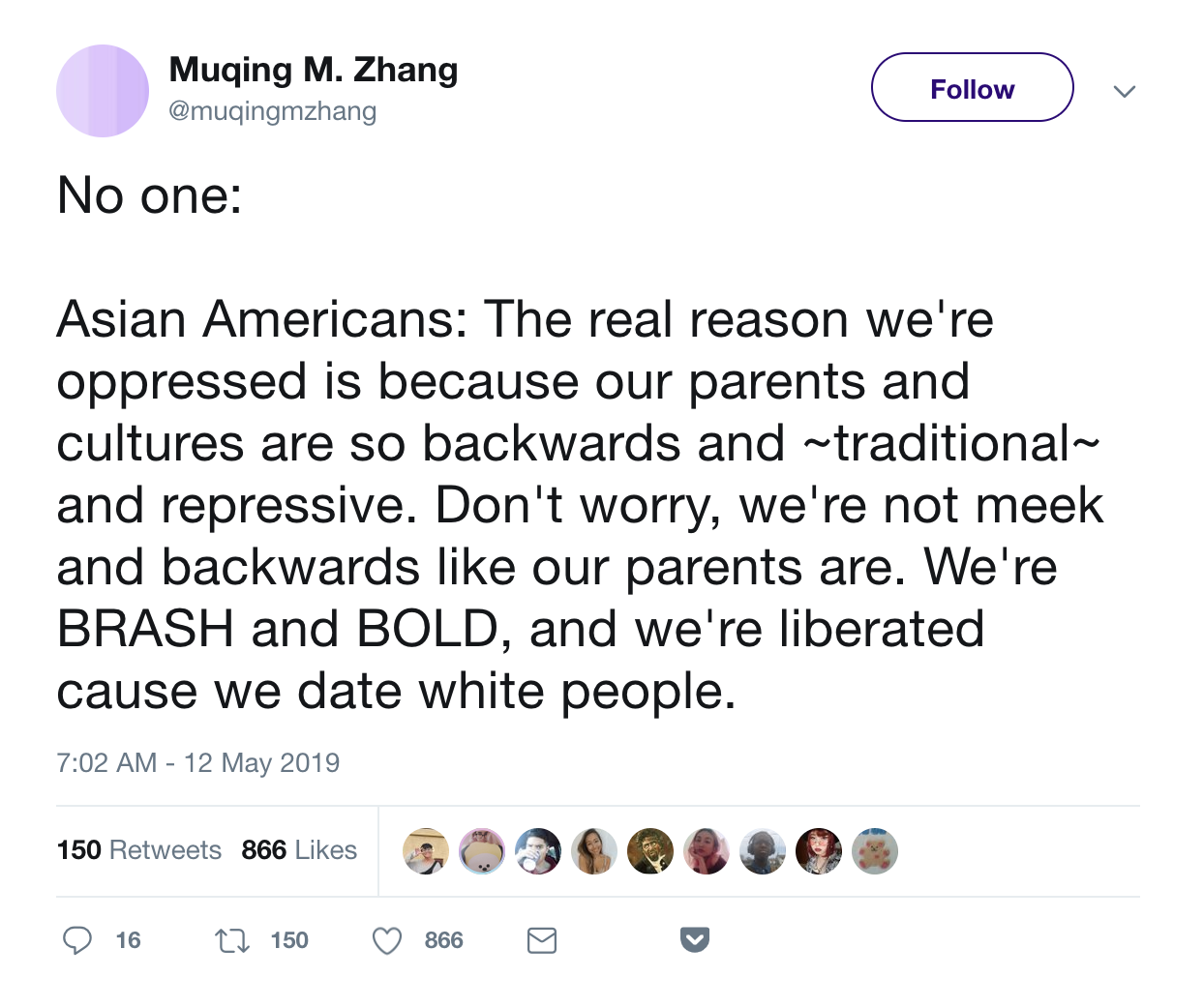

This trend is not limited to Asian creatives. Artists exploring the topic of identity are just retelling the pent up beliefs of their group. Everyone has met an Asian American who has told these stories about their believed “regressive” selves, often even to curry favour with white friends and associates. It’s that Asian cousin that jokes about how cheap their parents are while imitating their accent. Or that Asian friend that mocks the strange habits of new FOB students, that of course they don’t demonstrate because they’re so well assimilated. Our internal struggles have become a form of currency with which we buy acceptance in art and in life. And we seem completely unaware of the fact that we are telling a series of repetitive, and increasingly inane stories.

This lack of self-awareness leads to two problems with what we believe to be a form of rebellion. First, it totally misses the cause of this social pain, translating what is internalized racism into some sort of justification for rejecting your identity. Second, it is blind to the pattern that every other Asian American seems to believe that conducting life in this way is a form of transgression, which in reality makes it the status quo, and therefore not transgressive at all. Our grievances are misplaced, and they’re getting pretty damn boring.

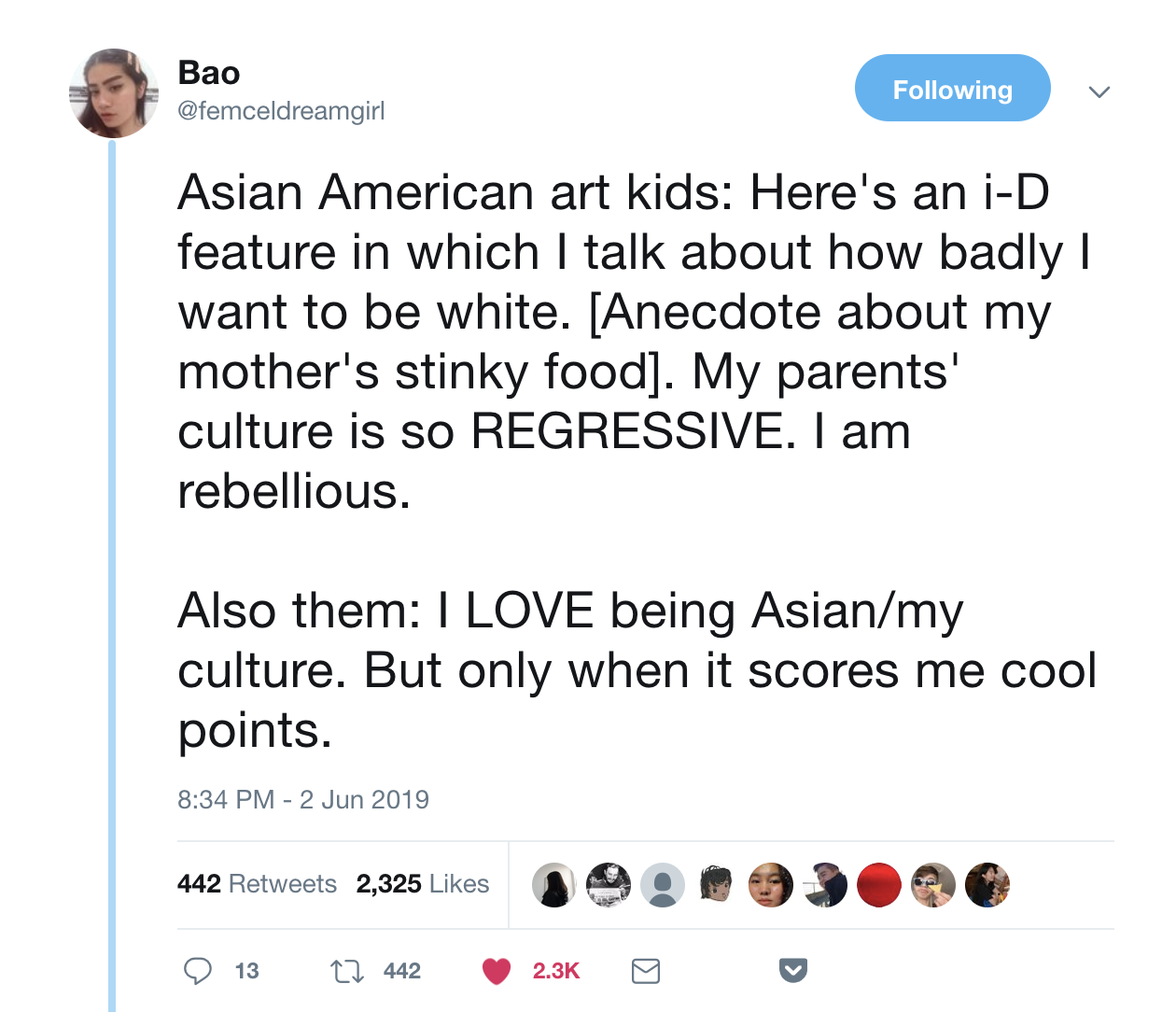

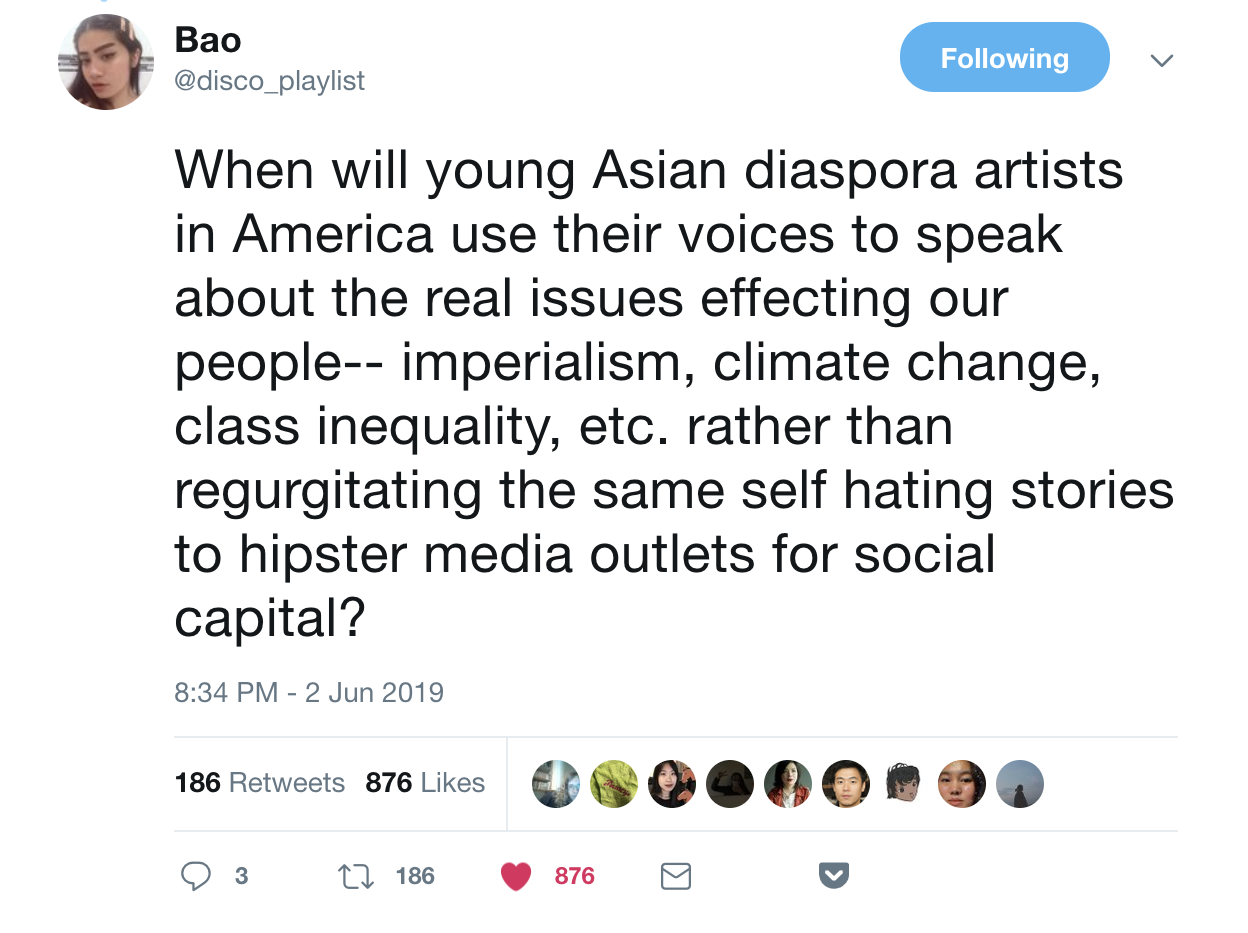

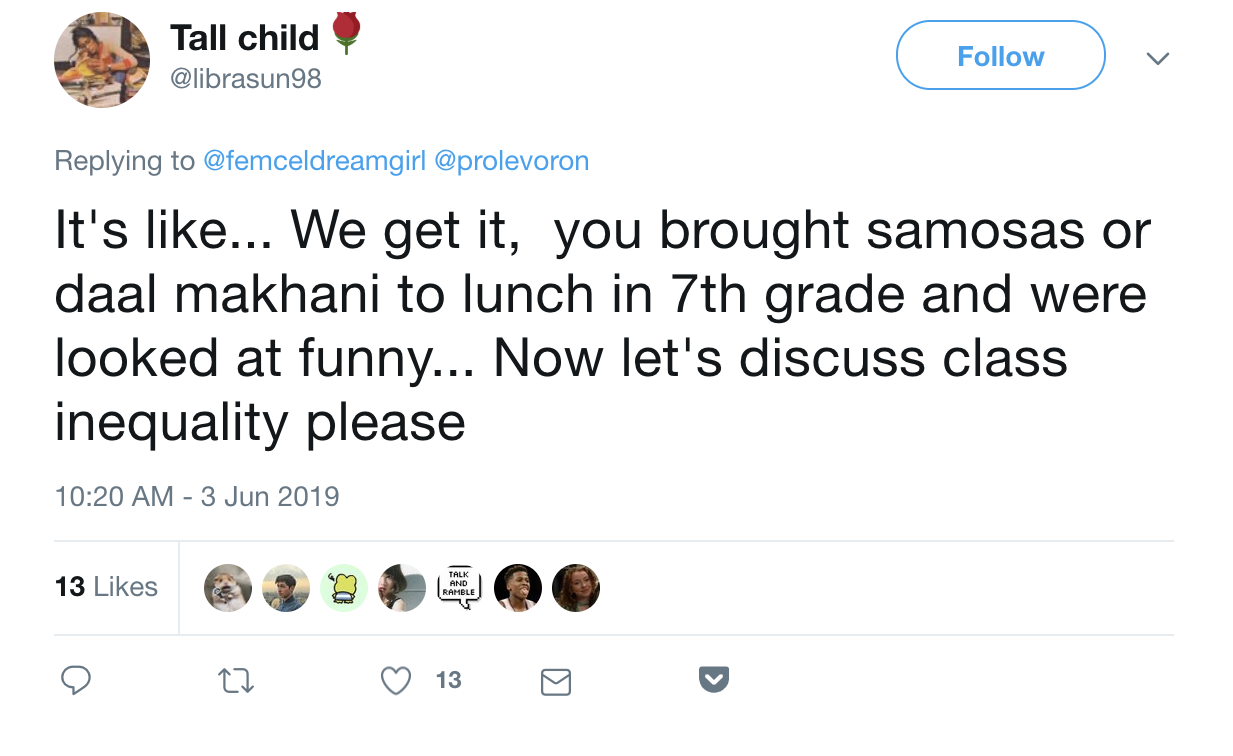

There’s been an awakening, as of late, to these tropes. I’m starting to see, perhaps for the first time ever, Asian Americans online (artists or otherwise) inflicting backlash against the backlash.

These takes are absolutely dripping with newly discovered self-awareness and critical disdain of the status quo. They see the social patterns that Asian Americans doze into and they question it, poke fun at it, and even fully reject it. We need that self-awareness to properly craft a counter-culture. Without it, we misdirect our energy and our criticisms. Without it, we don’t really know what we’re rebelling against. As Frank Chin once said while calling out sell-out Asian American writers, “They talk about the agony of the stereotype, but have no idea how to describe it.”

I can not say what the cause of this new trend is… if it’s the recent rise of representation in American media like Crazy Rich Asians and Always Be My Maybe leading to newfound confidence, or an explosion of pent-up angst against the upswell of racist sentiment from the 2016 election. But I want to believe that it is Asian American creatives (and writers, and commentators and, hopefully one day, “everyday” Asian Americans) doing what artists do best and finally creating something new.

So many other minority groups have been capable of seeing systemic causes of their anguish and Asian Americans need to catch up.

I believe this is the art of Asian American rebellion: To reject self-rejection. To instead question the underlying cause of our inability to fit in — is it actually something about us, or the world around us? So many other minority groups have been capable of seeing systemic causes of their anguish and we need to catch up. It’s a sight to behold: Asian Americans are slowly waking up to to the true reality and cause of their pain. It is becoming increasingly clear that the true way to rebel as an Asian American is to embrace your family, your culture, your race, and yourself.

Comments powered by Talkyard.