Not long ago, partly in an effort to escape the corrosive air of domestic politics in this lamentable age of Twitter and Trump, I visited China. It was my first time there. The air in the cities was cleaner than I had expected: the whirrs and whispers of electric scooters and cars in the alleys were signs of Beijing’s commitment to ecology. The political mood, on the other hand — what Politburo members were actually thinking amid a large-scale trade dispute — was harder to delineate from an outsider’s vantage, since it expressed itself behind the haze of state-controlled media.

China’s modernity, seen in its trains and glittering buildings, addresses the future in ways that are decidedly less cynical than the manner in which the Communist Party asserts control over its citizenry. We see proof of this in how it conducts surveillance over the country’s real and virtual topographies; in its strict, habitual censorship; in the stanched flow of cash and capital amid economic downturns. The nation, not unlike the United States, embodies titanic contradictions. Prosperity endures, but only amid a widening gulf between rich and poor. Technological wizardry expands yet circumscribes individual liberties. Privacy violations become rampant, all in the name of national security.

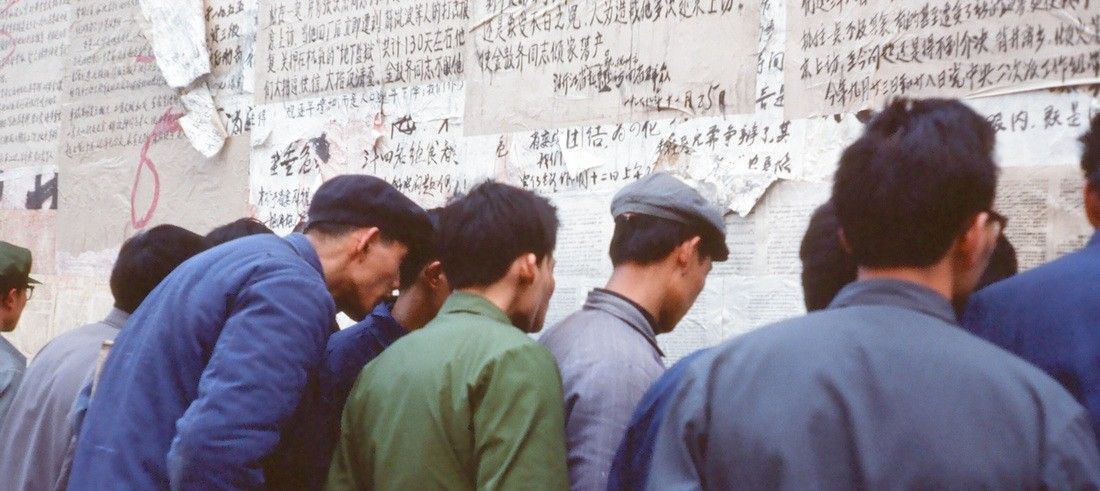

But hope persists. There was hope, arguably, in the “Hundred Flowers Campaign” of 1956; in Deng Xiaoping’s early support of the Xidan Democracy Wall in 1978; in the gathering of young protesters at Tiananmen Square in 1989. “Arguably,” because earnest feelings about freedom did not necessarily motivate Mao’s call to “let a hundred schools of thought contend”; “arguably,” because any flowering of dissent would soon prompt a clinical crushing of dissenters. If ever there were instances in which the Communist Party encouraged a variety of voices, Xi Jinping’s China does not seem to be one of those times.

It was against such a backdrop that I found myself in a Chinese bookstore, procuring a bilingual edition of recent Chinese science fiction. The anthology, Touchable Unreality, is currently unavailable in the United States. Its editor, Neil Clarke, writing on behalf of himself and writer-translator Ken Liu, sees in the book the “first stage of what we hope will be a bridge between two vibrant science fiction communities.”

Indeed the science-fiction genre is flourishing in China, so much so that observers have used the phrase “golden age” to describe its current phase. As both a literary artifact with social concerns and by extension a political one, the effort may invite questions as to how it eluded a publication ban. According to Clarke, at last year’s international science-fiction conference in Chengdu, China, politicians in attendance spoke about how important innovation, science, and the science-fiction genre was to the future of the nation. On the surface, they seem to value only the genre’s ability to promote the STEM disciplines. Regardless, the irony is sharp: the genre so often used to criticize authoritarian political regimes is also the genre that has been burgeoning under the watch of just such a regime. Could this be hope in a fantastic bouquet — another hundred flowers?

Its opening salvo, “Ether,” by Zhang Ran, may indicate as much. But it offers enough ambiguity as to who or what the main subject of its critique might be. Translated by Carmen Yiling Yan and Ken Liu, the story’s narrator is a 45-year-old bachelor who smokes cigars and quaffs whiskey, suffers an “aimless way of life” at a dreary job at the Department of Social Welfare, and reads absurdist news articles. He mocks protesters who mobilize against “the inhuman treatment of earthworms.” Initially, the latter image may sound like a lightly-veiled attack on the socially conscious, on members of the American left. But then the narrator opines, “If they really wanted to march and protest, couldn’t they have found an issue actually worth fighting for?”

Maybe not. For it turns out the world portrayed in “Ether” is stultifyingly bleak. The “sheer dullness” of “books, magazines, movies, TV” seems to proliferate, undoubtedly orchestrated by some invisible agency. The oppressive dullness “is murder on […] brain cells.” Even rock bands are “gutless” compared to those greater bands of yore, the Sex Pistols, Rage Against the Machine, and Nirvana.

Of course, the subjects under interrogation are not rock bands but rather digital-era democracies as well as authoritarian states, both of whose brokers — be they capitalist or socialist — have a way of distorting the field of available ideas. “Ether” contains no feeble condemnation of our time, of technological progress. Yet its themes have wider-than-expected reach. Who indeed can tell what is worth fighting for, if truth and reality are mediated and manipulated regularly by agents of benign and sinister intent?

One thinks of Churchill: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” The algorithms of a social-media platform can, and often do, situate users in echo chambers that reverb with familiar themes, so that the future experiences of users are determined, endlessly, by their past ones. Each participant inhabits a bubble whose curated comforts discourage escape. As individuals unfetter themselves from their communal obligations to enter into bondage with web browsers, democracies that have relied on cohesion gradually experience fragmentation, the way the walls of the Capitol might crack with time. In this manner, feelings of alienation have swept across this republic.

On the other hand, the illiberal state employs bureaucratic censors that can, and often do, cut and redact content with severity. The process results in a steady onslaught of repurposed rhetoric — a type of propaganda that, over time, largely engenders apathy or weariness in its target audience. Postings and articles become predictable, sterile, designed for mindless consumption. One outcome, among others, is an implacable feeling of numbness. Propaganda may supply the glue of cohesion, but at tragic cost: namely, a decline in individual assertion and a weakening of the human spirit.

For these reasons, “Ether” is transfixing; it invites such interpretations. And just when the narrator’s life seems destined for tedium, he encounters a mysterious woman in a hoodie, who introduces the narrator to illicit “finger-talking gatherings,” which are old-school chat sessions where participants sit in a circle, hand in hand, communicating to each other by finger-scratching characters (presumably Chinese characters, but not necessarily so) on one another’s palms.

These sessions are a throwback to less tech-saturated, more intimate times. They require participants to write and send one character at a time, to contribute to a “unidirectional flow of information” in an analogue network comprised of human hands, in that way bypassing the censors, or algorithms, or both. The outcome is a frank dialogue among rebels in analogue form. If this regression also sounds like a progression, it is also reinvigorating: finger-talking sessions electrify the lives of its cult-like members, and the narrator now experiences privacy and sheer joy through human intimacy, through a type of dialogue not moderated by unseen online forces.

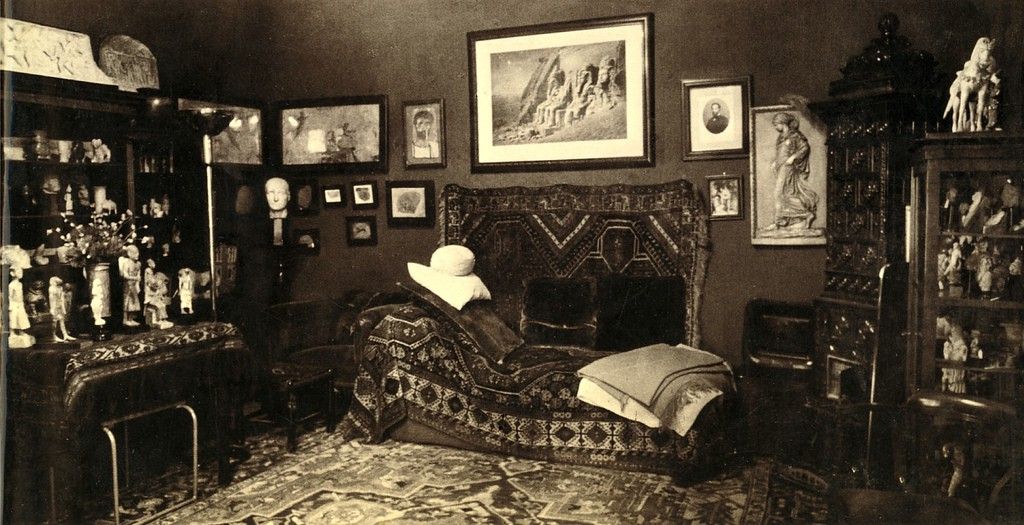

Applied to the real world, our world, the story addresses the popular desire to turn away and tune out: to delete one’s Facebook account, head to the wilderness, and reclaim that lost sense of liberation. “Something’s dying,” the narrator says to his psychiatrist early in the story. “Can’t you smell it rotting? The commentary on the news, the newspaper columnists, the online forums, the spirit of freedom is dying.” The psychiatrist, a “Swede with a beard like Freud’s,” prescribes him pills to suppress his “unreasonable fantasies” and reminds him of his “responsibilities toward our family, our society, even our civilization and our descendents.”

In the therapy session above, the setting, discourse, and diagnosis seem to emerge from the Western tradition. But its references to responsibilities, civilization, descendents, and the dearth of freedom gives the passage an interesting inflection: it contains underlying code that implicates socialism, with Chinese characteristics.

Indeed the world of “Ether” is a fascinating blend of both China and the United States. The bureaucracy described here is Beijing-inspired, but its population seems to be American: references are made to Steve Jobs, a “blonde girl,” the First Amendment, a Mexican, and a “red-haired guy.” At no point does the narrator specify the setting, its time or place. This ambiguity invites readers to come to their own conclusions about who the rebels and the oppressors are. This device in a way augurs the laying of Clarke’s bridge between two vibrant sci-fi communities and, more broadly, their nations, both of which have more similarities than their most nationalistic commentators care to admit.

Not all of the stories in his slim collection are as well balanced and consistent in sentiment. “Security Check,” written by Han Song and translated by Ken Liu, seems at first adamantly nationalistic and pro-Chinese in its depiction of New York City. Security agents are posted at subway stations; they wear black uniforms with red armbands. Jackboots are not mentioned, but they would seem at home here. In this topsy-turvy world, the People’s Republic of China happens to be the “world’s most secure country,” and the United States is merely an “experiment set up,” long ago, by the Chinese. The point seems obvious: China is good; the United States is bad.

But, upon final analysis, is the China depicted in “Security Check” really China? If the United States in the fictional tale is condescendingly described as a failed “experiment,” let us not forget that the socialist China of our time and space was also an experiment, to say nothing of how the historical United States itself was, politically and culturally, also an experiment. And does China not also employ security agents in its metro stations? The United States of “Security Check” unmistakably evokes China, and, if you persist enough to read beyond the climax, the latter recalls the former.

In the denouement, the narrator and a “beautiful Caucasian girl” board the Shanghai subway, which is “filled with every race from every continent,” a Whitmanian “multitude of passengers” who, “melding” as if in the currents of a river, seem to find cohesion with one another. The blending of settings so successfully executed in “Ether” appears to be a major trope here: Shanghai may signify itself, but it also conjures up New York’s messy, diverse democracy. So is China good? Is the United States bad? We never really find out, given the story’s destabilizing rhetoric.

These questions may be irresolvable, but perhaps Touchable Unreality escaped censorship because the Beijing authorities elatedly saw in these stories a harsh critique of Western society. Perhaps they failed to see, smuggled within the collection, a few daring and well-imagined commentaries on the problems and contradictions of China’s socialist regime. Or, better yet — and I realize I may be guilty of naivete or wishful thinking — perhaps they saw in it the vaguest strains of insurgent rhetoric, and welcomed it as a text whose themes seem to point vaguely toward some hopeful future. For even the Communist Party has experimented with democracy in local elections, regrettably retracting its efforts when it determined its citizens not quite ready. But if good fiction can move people and shape events, then this anthology, this sci-fi commentary about the way things are and what they could be, may constitute a spirited continuation of those efforts.

Comments powered by Talkyard.