RAZING THE LANDSCAPE

If you were to stand on 40 W College St. in Oberlin, OH, and face the front entrance of the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, you may feel as if you were confronting an architectural ghost. A similar sensation may be evoked if you were to face the Irwin Library at Butler University, One M&T Plaza in Buffalo, the Century Plaza Towers in Los Angeles, or the IBM Building in Seattle. These buildings are but a small sample of the enormous structural impact of a single homegrown American architect, Minoru Yamasaki, who is famously — or infamously — known as the principal architect behind New York City’s Twin Towers.

For me, the eerie effect of Yamasaki’s still-standing but unloved buildings is at its peak in the way the short, decorative facade of the Oberlin Conservatory resembles the lower-level facade that remained barely standing after the Twin Towers collapsed on 9/11:

While the Twin Towers were famously panned by architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable upon their completion in 1973, they quickly became the most iconic feature of the Manhattan skyline, and by the time of their ultraviolent demise 28 years later, they would become the most iconic buildings on the planet. The sanctity of Yamasaki’s architectural legacy was expressed by architect Bjarke Ingels, who supported rebuilding Yamasaki’s design in its original form (his suggestion was never seriously considered).

(After 9/11), my thinking was just to build the towers again the way they were… They were such a big part of the identity of Manhattan. When you watch Tony Soprano drive out of the Holland Tunnel, he can see the towers in his rearview mirror. They looked very strong.

Born in Seattle, Minoru Yamasaki developed his career and then-towering reputation as one of three or four principal minds behind the “New Formalism” school of architecture. New Formalism has had an impact on the American landscape far beyond his own list of projects, and for me embodies the mid-century era of American internationalism and refinement. Yet while the best-known buildings of other New Formalism architects remain in the American pantheon of national treasures — for instance Welton Becket’s Capitol Records Building, Philip Johnson’s Seagram Building, and Edward Durell Stone’s Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts — Yamasaki’s most famous buildings are known primarily for the notorious circumstances of their destruction and erasure from the American landscape.

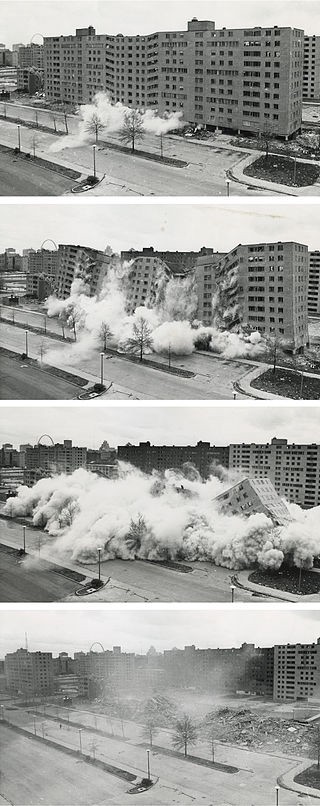

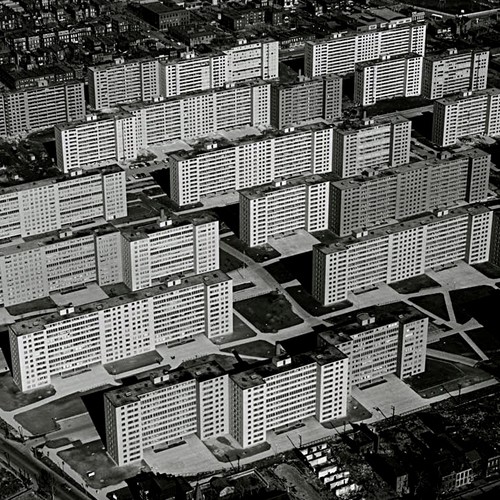

Aside from the most infamous building demolition of all time, Yamasaki is also directly connected to another infamous building demolition that has left a deep wound on American society in ways perhaps equally scarring as 9/11, but in ways less understood. The massive Pruitt-Igoe public housing project in St. Louis was designed by Yamasaki and was his first major commission. Construction was completed in 1954. It spanned 33 buildings across nearly 60 acres of land, a massive feature in the St. Louis cityscape and the grandest of experiments on how to solve the post-war housing crisis for African Americans as well as low-income whites under the aegis of President Truman’s Fair Deal. Pruitt-Igoe was designed to be racially segregated on a building-by-building basis, a practice which was declared illegal one year after their completion. The projects were a spectacular failure; maintenance standards were low, and poverty and crime were high. The project was such a monumental failure of policy that they were razed completely in 1971. Yamasaki’s first major commission lived for only 17 years, a lifespan 11 years shorter than his most famous.

The physical failures of Pruitt-Igoe was blamed in large part on Yamasaki himself, and architectural historians widely regard Yamasaki’s first ignominious failure as being the endpoint of modernist architecture itself. Recently, housing policy activists have coined this the Pruitt-Igoe Myth. It is a strange and unfortunate parallel to the accusations Yamasaki was confronted with posthumously that design flaws in the Twin Towers were to blame for their collapse, and that had corners not been cut under Yamasaki’s watch, they would have each survived direct impacts from fully-fueled jetliners.

Yamasaki died in 1986, and in his New York Times obituary, the Pruitt-Igoe failures so marred his legacy that it contained his apologetic plea to be forgiven, and a self-defeating concession that architecture has no role to play in social well-being:

He later said the plans had been altered without his permission. ‘’It was one of the sorriest mistakes I ever made in this business,’’ Mr. Yamasaki later told The Detroit Free Press. ‘’Social ills can’t be cured by nice buildings.’’

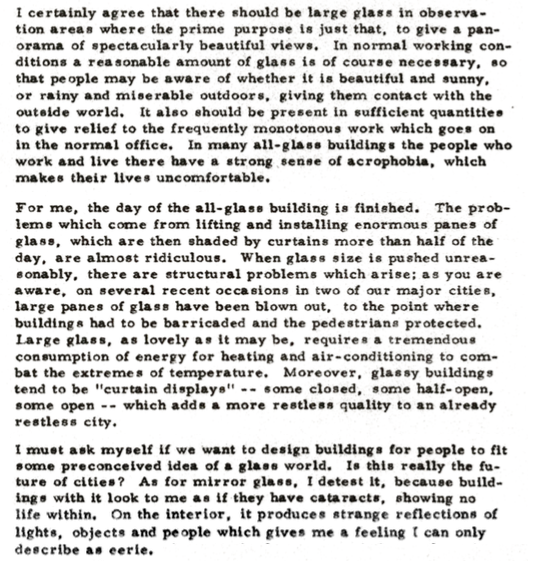

Though he appeared to surrender to his critics in his obituary, these were not to be Yamasaki’s final printed words regarding his legacy. In 2014, CLOG Magazine’s World Trade Center issue included a written response by Yamasaki to Huxtable, the vocal, Pulitzer-prize winning critic at the Times who panned his most famous creation on the occasion of its birth. Yamasaki’s response perhaps includes a prescient critique of why 1 World Trade Center — aka the “Freedom Tower” — has (along with all the other glass-shrouded and brittle Titans emerging throughout Manhattan) failed completely to capture the imagination and iconography of Yamasaki’s now-immortalized original:

ERASURE AND REPLACEMENT

The Corvette is the most iconic American sports car, and spans seven generations (from the C1 to the modern day C7) over six decades. Of the seven generations, the C2 — better known as the Sting Ray — is the most iconic. It debuted in 1963 and was produced for only five years. Of the Sting Ray’s five year run, the first batch is the most highly sought after, and was produced for only half of the 1963 model year before being re-designed to ease manufacture (each wheel alone consisted of seventeen separate pieces, reduced to just one upon redesign later that year). This batch-within-a-batch Corvette is the remarkably rare and highly prized “split window” Sting Ray.

There is quite a bit of history and mythology surrounding the men behind the design of America’s most famous muscle car, so much so that GM itself maintains an official Corvette Hall of Fame to enshrine the names of these men for perpetual reverence. This is, of course, of no surprise. Classic American supercars symbolize authentic American culture in a way that few, if any, other commodities can claim. The faces behind the ’63 Sting Ray are the faces behind America.

One of the men most principally associated with the design of the Sting Ray is a Japanese American man named Larry Shinoda. Born and raised in 1930’s Los Angeles, Shinoda grew up playing in the arid fields of the Manzanar War Relocation Center in California as a child prisoner of the Internment. In his twenties, as a free man, he displayed a preternatural talent for designing and racing hot rods. An intemperate student, Shinoda left art school before graduating and went straight to work for Detroit, rising quickly through the ranks at GM under the legendary auto designer Bill Mitchell. To those who follow American car design, Shinoda is a name associated as the lead designer not only of the ’63 Sting Ray, but also later works of significance including the Sting Ray convertible and Mako Shark, the Boss 302 Mustang, and the Jeep Grand Cherokee.

The mythology of GM’s Corvette program of the late 1950’s and early 1960’s revolves around an internal corporate feud that evokes the better popularized feud within Apple Computer between Steve Jobs’s Lisa program and Jef Raskin’s ultimately successful Macintosh program. One camp at GM was led by the brash and iconoclastic Bill Mitchell, the other by the aristocratic Zora Arkus-Duntov. Shinoda was the chief design lieutenant on Mitchell’s faction. The question of which of these two men should represent the true face of the Sting Ray — and thus the Corvette itself — is one that seems to be a dispute that is very much alive today.

GM established its Corvette Hall of Fame in 1998, and kicked it off with a founding class that included both Arkus-Duntov and Mitchell, as well as Shinoda. A Hall of Fame must by definition leave out those who have not merited such a distinction, a fact that can be discerned from the diplomatic compromise language GM used to describe Shinoda’s legacy:

Along with Bill Mitchell, designer Larry Shinoda has been closely associated with the Corvette Sting Ray, the stunning design that debuted in 1963.

The non-exclusionary phrasing of the term “has been closely associated” opens the door to questioning the seemingly dominant narrative provided by Jerry Burton in which the triumvirate of Mitchell, Arkus-Duntov, and Shinoda are portrayed as the principal progenitors of the Sting Ray. A separate narrative, however, has been offered by a GM designer from that era named Pete Brock, author of the 2013 book Corvette Sting Ray: Genesis of an American Icon. In 2014, Brock appeared on an online episode of Jay Leno’s Garage in which he discusses the design of the Sting Ray, and Shinoda’s name is left out entirely despite repeated mention of the other ’98 inductees (including mentions of Ed Cole and Earl Harley, both more senior executive managers at some remove from the Sting Ray project). In a later episode of Garage in which Leno discusses the Sting Ray with restorer Mike McLuskey, Mitchell and Arkus-Duntov are mentioned by name, but Shinoda is again conspicuously ignored.

It seemed strange to me that someone as tightly associated to the Sting Ray as Shinoda would be ignored on Leno’s Garage, and perhaps it was the case that as a lieutenant to Mitchell, he simply seemed too junior or subservient to be worth a mention. But it turns out that there is a campaign put together by a Corvette collector named Darwin Ludi for Pete Brock’s inclusion in the Corvette Hall of Fame, and to be recognized as a design lieutenant under Mitchell with equal or greater weight than Shinoda. A letter of nomination was drafted and circulated to the Hall of Fame to nominate Brock for inclusion in the 2016 class of inductees (Brock was not included). Curiously, although neither Brock nor Leno make any mention of Shinoda at all in their discussion about the Sting Ray, the letter itself (which Leno apparently signed) puts the issue of Shinoda’s credit front and center:

Larry Shinoda is given full credit for the final design of the 1963 Corvette and rightfully so, however Peter Brock’s renderings of the 1959 Stingray racer show that his design concepts were included in the final design of the 1963 Corvette.

We must not forget the history of how the Corvette evolved and both Larry Shinoda and Peter Brock are very important aspects of that history. Larry Shinoda is already in the NCM Hall of Fame, it is now time to include Peter Brock into the Hall of Fame.

I find at least two curiosities here. The first is that the letter makes no mention of the inclusion of either Mitchell or Arkus-Duntov in the Hall of Fame, only Shinoda. If the letter were to simply state that Brock’s contributions were worthy of distinction, then it should have mentioned at least Mitchell as well.

The second curiosity is that Brock holds nothing back in his public praise for Mitchell being the real man behind the ’63 Sting Ray, lavishing praise on him both on Jay Leno’s Garage and in his own book, with nary a single mention of Shinoda. This directly contradicts Darwin Ludi’s position that Brock fully recognizes Shinoda’s credit, and simply wants to be included as an equal:

“Peter does not take any of the credit from Larry,” Ludi said. “He has the utmost respect for him. His renderings of the 1959 Stingray racer were ultimately used to design the final product by Larry Shinoda.”

Pete Brock, it seems, is on a quest to erase Larry Shinoda from American design history, and to replace Shinoda with himself, if not from the Corvette Hall of Fame (such a process being unavailable altogether), then from the public consciousness.

Nonetheless, Brock is an undeniably illuminating authority on car design, and he gives what I think is a remarkable insight to the nature of the Corvette’s status as an American icon:

A lot of the ideas of what an American car should’ve been was, that you got into this living room and it took you some place. The whole idea of a sports car really didn’t make much sense at all because there was no sport. We were driving in straight lines. So the whole midwestern idea of doing this car was very very foreign. And if it hadn’t of been for people who had a little more understanding of European cars — Bill [Mitchell] of course had traveled over to Europe and seen all those cars over there, and all those things influenced him into doing it.

Indeed, the C2 Sting Ray is a massive departure from the original C1 design, a car which does quite resemble the living room couch on wheels Brock accuses it of. The C2 is a radical transformation, and much more closely resembles the famed Jaguar E-Type produced in the UK at the same time (a car which figures famously into Don Draper’s dogged pursuit of Jaguar as a marquis auto client in Mad Men). The C2, it turns out, is mostly an American appropriation of a European design heritage.

This calls into question a lingering belief among car enthusiasts that Japanese sport coupes that were sold into America on the heels of the Sting Ray — in particular the nearly ubiquitous Datsun 240Z — are simply bad knock-offs of the E-Type and other European coupes. With Shinoda having taken official credit for America’s most famous knock-off, and 240Zs becoming collectible automotive art in their own right, one must begin to question whether the popular conception of white mid-century American men are in fact the proper faces behind the American sport coupe heritage, and whether it is an Asian face that should instead come to mind first in the popular imagination.

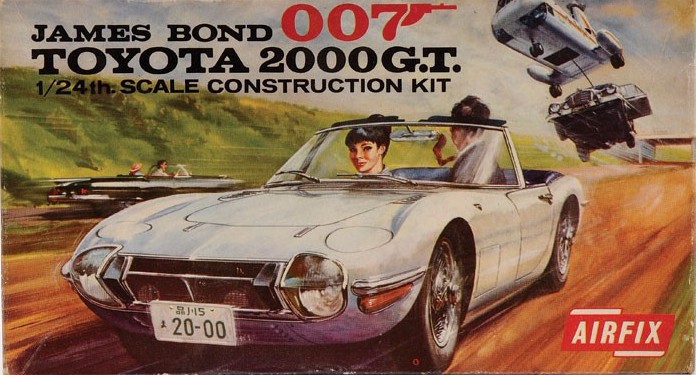

The global car collector market is starting to question this as well. A ’63 “Bill Mitchell” Sting Ray in mint condition can be had for about $130,000. A ’67 Toyota 2000GT — famously driven by James Bond himself — would take nearly ten times that amount.

NEGLECTING THE CONTRIBUTION

A few years ago I convened with old friends in LA. I’m not alone in having an aesthetic fascination with LA, quite probably the ugliest of the major American cities. I demanded that our first breakfast be at the iconic Pann’s Diner. Pann’s is situated on an awkward triangular lot in Ladera Heights across from a Ross and next to a Mobil, and does not serve any breakfast dish of sufficient repute to justify visiting Ladera Heights while on vacation. The major draw of Pann’s is the incredible Googie architecture both inside and out. To walk into Pann’s and occupy a red vinyl booth is to immediately understand Quentin Tarantino’s aesthetic inspiration for Pulp Fiction. Pumpkin and Honey Bunny execute their famous hold-up in the since-demolished Hawthorne Grill, a restaurant co-owned by the owners of Pann’s.

Along with the Norms Restaurants micro-chain, Pann’s is perhaps the most famous of Southern California’s vintage diners. Close behind is Lem Quom’s Formosa Cafe with its earlier, Golden Age mystique. These diners are literally where American movie mythmaking takes place, serving repeatedly as the sets for era-defining scenes in the aforementioned Pulp Fiction, Swingers, L.A. Confidential, and countless more. One of American pop-art master Ed Ruscha’s most beloved paintings is entitled Norms, La Cienega, On Fire.

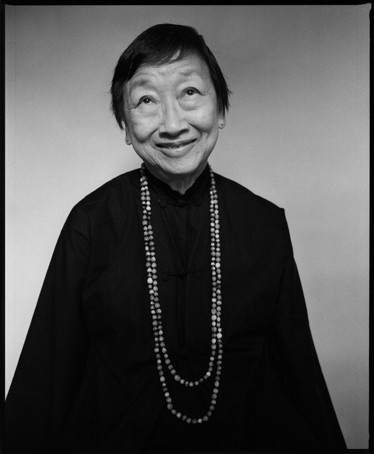

As these diners and other physical icons of authentic American culture are elevated into the abstract conceptions of Americana, it becomes more difficult to perceive them as the particular works of individual designers. For me, they seem to form more of an aesthetic that is American, vintage, and by default white. For Pann’s and Norms, it takes some digging around to discover that they are the designs of Helen Liu Fong, a Chinese American architect. Her name is notably absent from Pann’s official online history of the iconic structure, which credits its existence generally to the Panagapoulous family’s “continued investment in Googie style architecture,” with no other names mentioned.

There is a curious link between Fong’s most famous diner and a more substantial act of high architecture by another, much more widely recognized Chinese American architect, I.M. Pei’s National Gallery of Art East Wing in Washington D.C.. Hand-selected by Jacqueline Kennedy, Pei was tasked with solving the same basic conundrum as Fong: how to build a structure on a odd, triangular lot. Pei and Fong’s solution to the triangle problem are, in my opinion, two of the (fittingly) three most iconic American solutions that exist, the third being of course the Flatiron Building. Here are Fong’s and Pei’s solutions:

A further curious link exists between the Fong and Pei triangle solutions: as with Pann’s website, the Smithsonian’s website information of the East Wing building also contains scant or no mention of its architect at all (despite plenty of other names mentioned, mostly donors and philanthropists).

RE-EVALUATING THE AMERICAN LANDSCAPE

The most famous building in modern world history. The most iconic American muscle cars ever built. The sets of America’s epochal movies. The gallery of its most famed visual artists. The physical spaces and artistic iconography make up how we think of America. I’ve seen a Warhol exhibit in the East Wing, I’ve had a plate of waffles at Pann’s, I grew up on old episodes of Stingray, and I like everyone else stared in disbelief as the Twin Towers exploded, burned, and then collapsed. And, I’ll admit, in these experiences I did not see, notice, or even imagine that I was inhabiting Asian American creations.

The reason I find Yamasaki, Shinoda, and Fong so interesting is not simply “we” were there too (I don’t find much personal connection to any of them) but that their enormous influence on mid-century America makes us question our assumptions about that history and the culture that existed back then. I immediately wrap an assumption of “even though they were Asian they were still able to make it.” But what if we are getting something completely wrong about mid-century America, and therefore, misinterpreting the culture of an era which we seem to be enshrining for the present and future? There is a force which tends to erode their contributions (and all non-white designers and creators) so that the very culture within which they flourished is retroactively white-washed.

In 2012, the Chinese American Museum took a step towards rectifying this failure of the imagination in their exhibit Breaking Ground: Chinese American Architects in Los Angeles (1945–1980). The exhibit focused on mid-century Los Angeles architects Eugene Choy, Gilbert Leong, Gin Wong, and of course Helen Liu Fong. That an exhibit of such narrow focus — narrow in time, place, style and nationality — would produce enough subject matter to warrant its own exhibit, suggests how deeply Asian American design and architecture could be defining the space that we imagine as America without us even considering it, much less knowing it.

It is a mere assumption, reinforced by a social tendency to deny and suppress evidence to the contrary, that the American landscape and its cultural symbology was created mostly by white men of a certain empire building age. Yet it only takes an afternoon of Googling to discover that “Asian America” is much more than a census checkbox some government bureaucrat came up with — a popular and pessimistic line that many Asian Americans of a certain libertarian bent insist is the case. It turns out you can actually find Asian America on a map (various links provided above).

Comments powered by Talkyard.