After the death of my Adoptive mother I received a packet of Adoption paperwork in an aged manila envelope from my sister. For more than a year she had commuted from PA to Long Island to help our reluctant Adoptive father deconstruct the horde in our childhood home.

The packet contained the correspondence around my adoption, medical records, and some progress reports and photos I had never seen. In addition, my sister sent an envelope that contained a stack of 50 plus photos and paperwork from the foster children my mother had sponsored from 1970-1973.

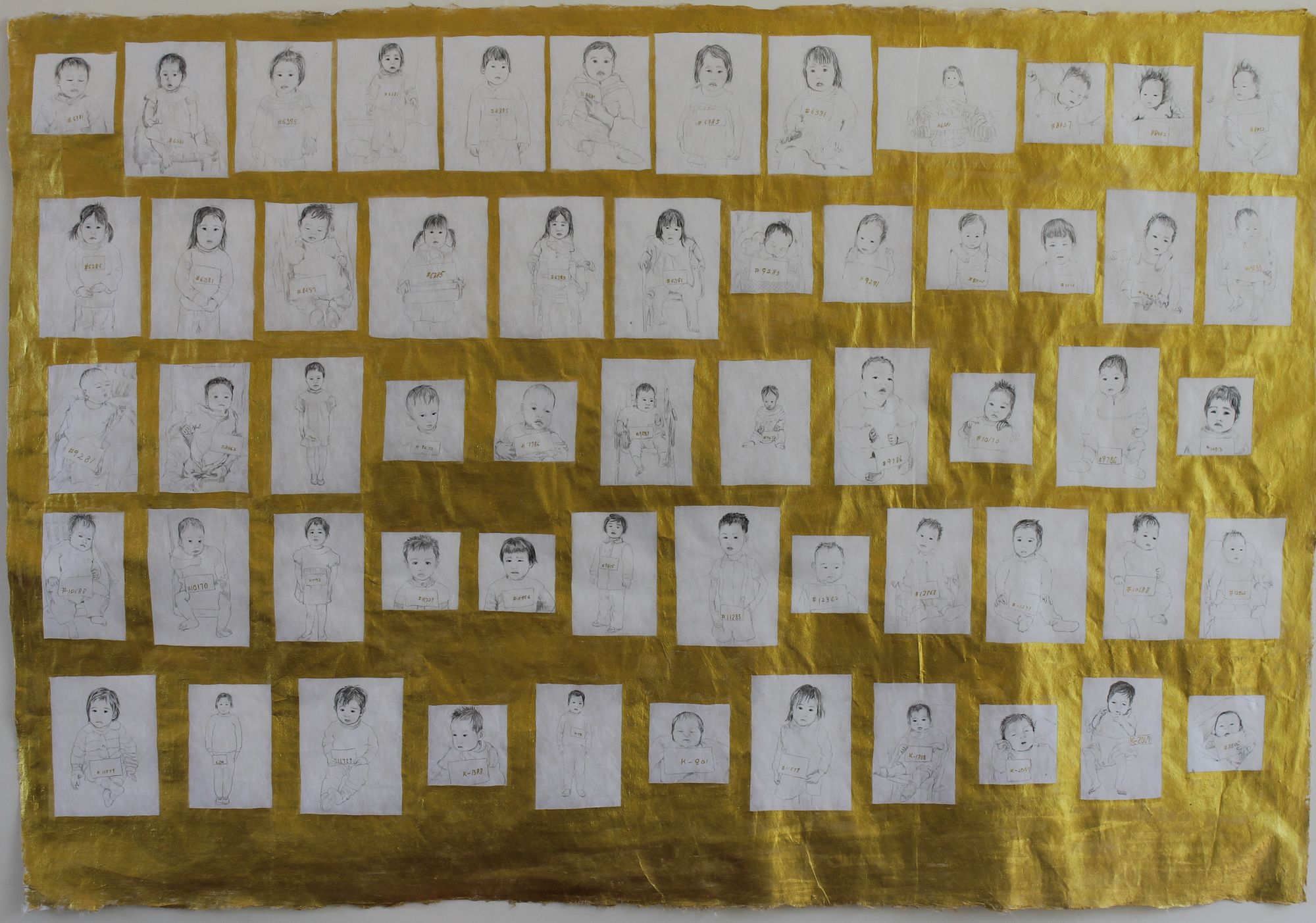

At the start of the pandemic I took a fresh look at the photos. The files were weighing on me, waiting on me. The photos and reports read like a diary of desire, consumption and promise. Here is one child, now another thanks for the money, now we have another. There are multiple Certificates on heavy paper with embossed seals and official signatures congratulating my mother on her part in supporting a child up till their adoption.

I am reminded of the many certificates of achievement my sons received in Elementary School: best attendance, best test scores. I felt burdened by the images and the files.

Until recently, I had avoided addressing the story of Adoption in my Art. In Art school there were some brief forays, an image of an illegible birth certificate, a drawing of a Kewpie doll with patterns of floating, falling Asian dolls in the background. I purposely stayed away from the marginalizing identity politics. Confined like so many by the Pandemic, these photographs compelled me to begin.

Golden Ticket

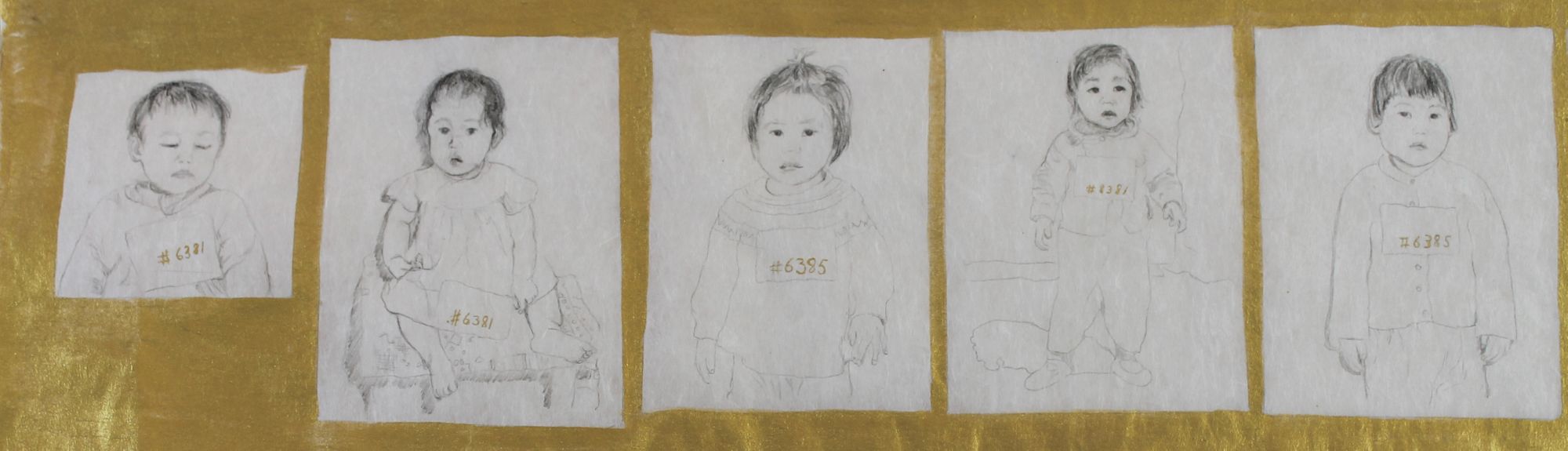

I began with the small black and white adoption photos. I recall as a child pouring through the Holt Adoption Agency’s monthly newsletters filled with baby pictures. Just as I poured over the Sears Christmas catalogue toy section every year. In my family we did not make lists as money was an issue. I focused on one toy, I could dream of more, but I could have just one.

The Holt newsletter displayed a carousel of babies and children who looked like me, needing a home, needing a family, or perhaps just needing food. The individual truths could only be known by the faces not shown in the catalogue.

The task of mining those truths has been the work of Adult Adoptees who search with an ever-present need to find something, someone, some understanding too often irreparably lost. And still some of us will always live in the island of the lost toys regardless of whether someone claimed to have found us and put us in new homes.

In 1995, Cho Duck Hyun, a Korean Artist showed works of baby portraits in wood boxes. I visited this exhibition at the ICA in Philadelphia. The babies are anonymous and I don’t know where he drew the photos from. Reminiscent of the baby boxes used to surrender babies the boxes are stacked into the corner like a pyramid. I remember feeling so moved by this exhibition. Included are larger family portraits rendered in pencil on mulberry paper.

As a Korean adoptee the people and the family portraits though peripherally moving, felt distant as the oceans and continents separating me from the place I was born. I stood very much in exile, outside of his reflection of Korean history. Fifteen years later I still see the images as his Korean reflection and I admit to feeling those babies in boxes were not his to speak for.

As a phenomena, the exporting of a nation’s children is a loss and a tragedy that may be rooted in Eastern and Western colonialism, and this is an integral part of our mutual Korean legacy. But as one of the consequences of this import export trade I feel the faces in those dark boxes have stories that are only marginally his to share.

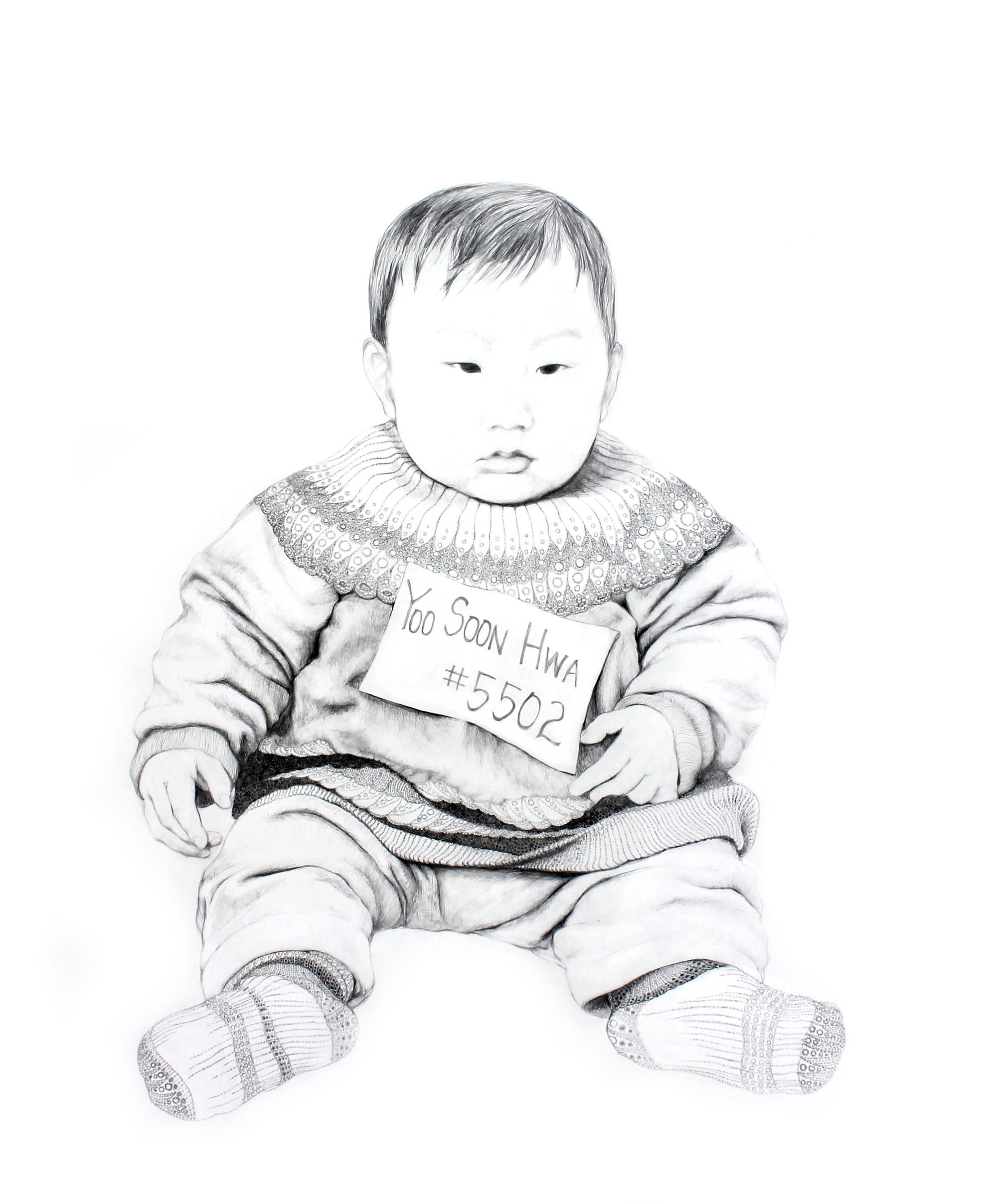

After having read all the foster care notes and correspondence around each “orphan” in my mother’s file, I drew. Faces, expressions, bodies, gestures, postures and placards with numbers all inhabited my visual vocabulary in a new way. I have never studied or even looked at Korean faces so closely.

In an age obsessed with selfies and since the advent of the photographic portrait, the eye of the camera has captured us in it’s own pictorial cell. These staged photos brought me to a moment; a moment before the sale, during the time of surrender, a time of limbo, a time of unspoken truths. Mute like a body in trauma, each photo offered a new face for the same expression.

As I drew each image it became harder emotionally and I found myself embodying the questions that so many must have wondered at that moment; what next? What happens now? And knowing only my own answers and the outcomes of so many stories told by other Adult adoptees I dreamed and hoped for these children, my peers in age and circumstance. And as I drew, I fell in love with them too. For some adoptees like myself this photograph is all they have from the before time.

These are our origin stories. Although I was not one of the sponsored babies in the collection, I was the first of three to be adopted by my American family. I included my first photo, taken at 11 days old. I was told that I had been left at the doorstep after my birth. It would take almost 50 years for this image to travel to me in the present time.

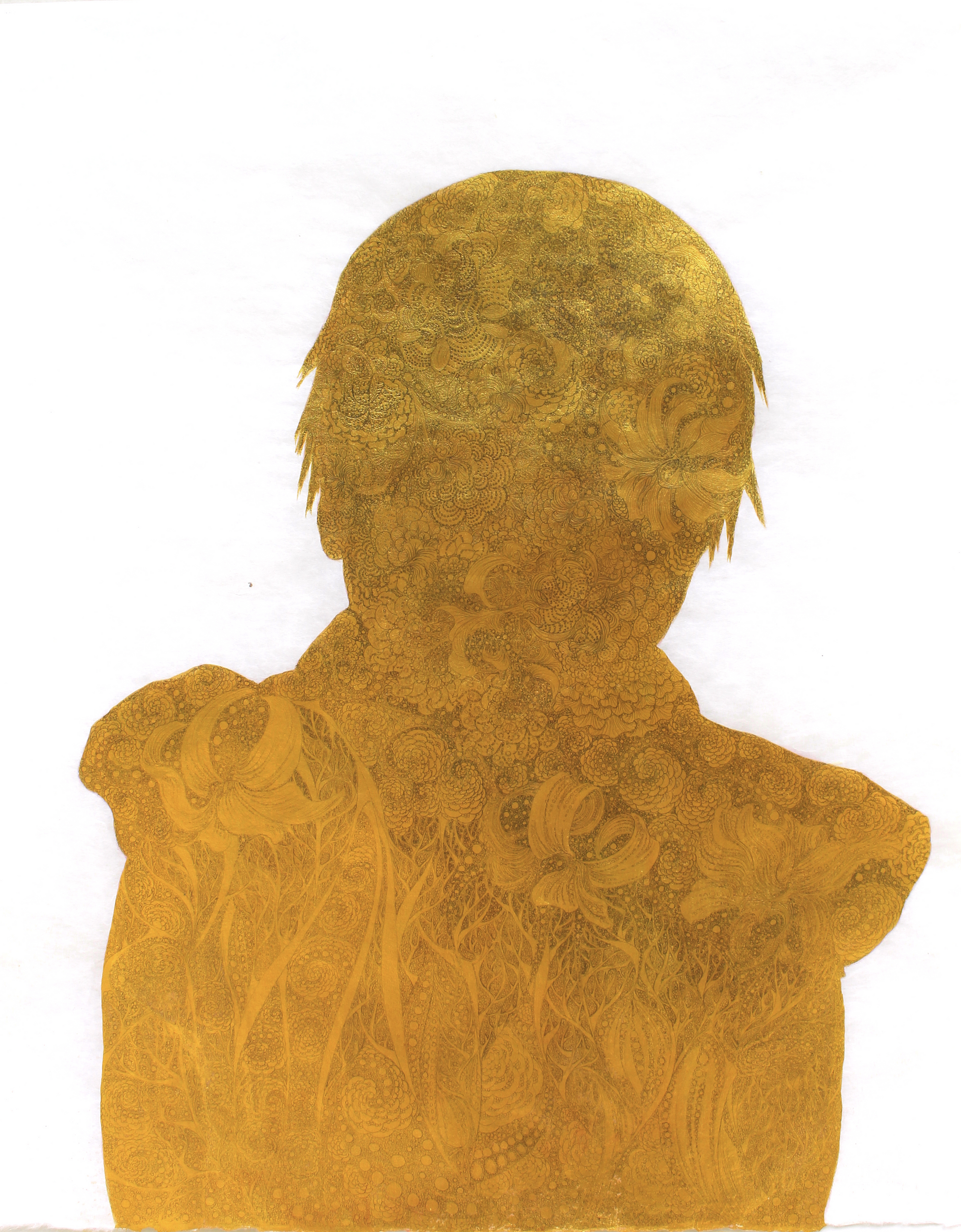

After completing the Golden ticket I moved back into the safety of abstraction and metaphor. Thus darkened seeds and silhouettes of my personal adoption photo gave me time to sit in the silence with my uncertainty. When I was ready I began my own large portrait and then ventured on to the difficult task of rendering my older sister’s photo.

Her portrait tortured me in ways that have nothing and everything to do with mechanics. In the photo she is according to her papers, five years old, and will still have three more years in the orphanage before she is adopted.

I look at the photo and I see traces of my sister, the last vestiges of an unknown story. The lighting in the photo is stark and unflattering though she is wearing a puffed sleeve dress.

I look at the picture and my mind cycles through the years of images I have of her in my memory. We shared a room my whole childhood. Though she arrived a year after me, she is five years my senior.

According to her file she was bloated from malnutrition, and one of her pictures show cheeks tight and full on her face. I never remember that. She was smaller than average too. She would never quite reach 5 feet as a woman.

Regardless, her status as an older sister was never questioned. She was tougher than I. She had learned things that no one will ever know in her 7 years in Korea. She was labeled a “mixed” baby not “pure Korean”, a transgressive status that followed her from Korea to our family.

Later she would do a DNA test and find there was no trace of foreign western blood. I was labeled “pure Korean.” Lucky to be raised by a foster family and not in an orphanage.

She also had thin hair, a quality my mother would pin to her as parents do. And so she was relegated to short awkward boyish haircuts, such was our Adoptive mother’s reasoning.

My hair on the other hand was thicker and therefore allowed to grow longer and longer, like Rapunzel. It would seem that our status was set long before our Adoptive mother picked up the mantle.

Intention, perception, history, beliefs and observational data made the work of transforming my sister’s 2x3in., 51-year-old black and white photo from 1968, a struggle worth having. I drew, erased, re-drew, measured, remeasured, despaired, started again, got lost in the relationship of features, forgot the whole, erased, re-drew, reshaped, discovered, and finally understood and accepted the nature of the shadows until I found her.

I knew there would be a moment when I looked at the picture, when I held it to a mirror, and I would see her unmistakably looking back at me. I could not guarantee the moment until it arrived. And then there she was shining at me like an alabaster bust, my precious sister modeled in the white gaze of desire.

With the drawing complete now, I see her looking at me. All the dark traces of history erased and unknown; an orphan masked in whiteness waiting to become part of our assimilated American dream.

Looking back on a time of unknowns and powerlessness through the eyes of a child as well as through the eyes of a mother, this has been heartrending work. Though primarily an abstract artist I am more comfortable in the realm of patterns and metaphors. Subconscious truths revealed in my abstract work hide their rough edges in transformation and beauty.

Deconstructing the generalizations of 50 year old black and white photos has led me to research the history of the Korean war and the cultural inheritances I have always been aware of, but never truly understood.

This portfolio confronts historical truths of Korean adoption, colonization, assimilation, commodification, religion and families. The research and the work has also opened my understanding of my place as a woman in the context of Korean American cultural legacies.

The Adoptee Healing Portraits

It was a natural progression for me to put a call out for other Adoptee Healing portrait participants. It is not a small thing to share one’s adoption photo and I take the commitment seriously. I explain my process and interview interested adoptees and then we sign agreements regarding the work and how the image is to be used.

I am doing the portraits because I have been told it is healing work by my recipients. I hope that in some way the work gives witness to each Adoptee’s innate beauty in the before time. The drawing and the time spent on drawing is the most honorable love I can give.

It is my hope to put together an exhibition of the portfolio of work within the next two years. I am still exploring where and when that may occur.

Comments powered by Talkyard.