Here at Plan A, we’ve spent the last two plus years immersed in online Asian spaces. We’ve met a lot of great people, but we’ve also met a lot of scum online, as well. But that’s expected, right? In anonymized online spaces we expect to see all-things-racism. Those encounters feel almost abstract in that they seem to not have true consequence. You can block the assailant, let yourself be distracted by cat memes further down in your feed, or hell, just log off.

But in contrast, to experience racism in meatspace is jarring. To even hear about a friend or friend-of-friend encounter something shitty purely because of their race is like being punched in your own gut. The first racist encounter I heard of in Toronto since the coronavirus hit our city absolutely floored me, and I had trouble believing it was real. The story was so egregious, it bordered on parody, partly because I think Asian Americans are not used to confronting a blast of aggression at our entire community all at once. We are used to a lifetime of microaggressions, or the slow asphyxiation of our careers by the bamboo ceiling, or the occasional isolated “chink” spat our way, especially when living in a liberal city like Toronto. But today with nCov, things have gone from 0 to 100 in just two weeks worth of news coverage.

We are used to a lifetime of micro aggressions, or the slow asphyxiation of our careers by the bamboo ceiling, or the occasional isolated “chink” spat our way.

And that’s what’s happening now with the coronavirus coverage at peak. Here in Toronto, there was a palpable change in the air as we received our first novel coronavirus patient two weeks ago, and up to our sixth now in Canada. Stories started cropping up everywhere of Asian Americans butting up against explicit discrimination from all over — not just in the news, but from our network of friends and family.

But what if this sudden scuffle with explicit racism (as opposed to the lower key racism we deal with every day) can actually do good for Asian Americans and how we tolerate racism and ourselves? What if the shock of aggression serves as a reminder of the threat under the surface, and what if those learnings stay with us after this crisis is long over?

The nCov crisis is dredging up a lot of issues we have with ourselves

I’ve heard stories of Asian Americans secluding themselves from the outside world, for various reasons related to coronavirus. One baffling reason is that Asian Americans are not doing this out of fear of discrimination from non-Asians. Rather, we’re doing so out of fear of causing discomfort to non-Asians with the mere sight of our supposedly diseased selves.

I’ve heard stories of Asians cancelling dim sum plans with white people because they’re worried that they’ll make them feel uncomfortable eating Chinese food at this moment, like somehow the source of the virus could magically manifest suddenly in a Toronto restaurant (let’s remind ourselves that no one actually knows what the origin of nCov is yet). There are stories of Asians in public transit holding in their coughs or getting nervous when they feel a sneeze coming on, because they don’t want to frighten other people on the subway or streetcar.

This highlights the “guest mentality” of Asian Americans: the internalized idea that our presence here is perpetually illegitimate, even if we were born and raised here. That we need to always be polite and subservient to other people who are really our equals — always a guest and never a native. Over- consideration of others’ feeling suggests that we have ceded our right to being respected at all times. The threat of coronavirus has caused these feelings and behaviours to seep out and multiply tenfold, so it’s in plain sight. It’s a chance for us to recognize it, criticize it, and correct it in ourselves and Asian Americans around us.

The nCov crisis brings to light issues we have with our own community and assimilation

The nCov crisis has revealed the distrust we have of our own communities, as well as the deeper issue of internalized racism. In a panic, many Asians have adopted an “every man for himself” mentality, abandoning our own communities in fear. A couple weekends ago, on Chinese New Year, my dad cancelled our annual visit to the local Buddhist temple, concerned that somehow the nCov virus might be carried by one of the thousands of other local Chinese visitors during this peak period. This is all before the first case of nCov was even reported in Toronto. It was a challenging thing for me to hear, my own father discriminating against people like himself based on paranoia.

The gut reaction from too many assimilationalist Asians, when they hear something like this, is to play the familiar “I have backwards immigrant parents” card, like it’s the only trick we have up our sleeves for dealing with and explaining behaviour like this. But really it should be taken as a moment of empathy for all generations of Asians who are thrown into this situation. My dad listens to the news and these days it’s been 98% corona virus bullshit. He’s concerned, and I get it. There’s no reason for me to capitalize on this as a way to distance myself from my own dad in order to come off as some sort of “Good Asian™”.

2nd generation Asian Americans are going to be confronted with the question of whether they side with Asians as a whole, or differentiate themselves from the supposedly “backwards” old guard and “dirty” newcomers. Everyone has seen Asian Americans pit themselves across from FOBs. This is the assimilation question once again, exacerbated to the nth degree because we finally have to deal with real explicit racism that makes us feel like we need to take sides to make it out alive.

When this tweet was making the rounds, I was surprised by how highly embraced it was. It reinforces this dangerous narrative that we’re only “good” if we’re integrated, and if the boy in the story was instead unable to speak perfect Italian, he would somehow be worth less. Or worthless. To embrace this mentality is to reject solidarity with other Asians, and to only valorize the parts of us that are closest to whiteness.

Whether or not this incident was real, we see this attitude towards assimilation exhibited by Asian Americans often — during this crisis and in normal times. We see it every time someone tells an Asian American to “go back to your country”, and they respond with “But I’m an American citizen”, instead of giving the only correct response, which is “FUCK YOU”. We need to avoid using the implication that somehow the “other” Asians are the problem, and we’re not because we’re born here. Or because we’re Korean and not Chinese. Or because we’ve never set foot in China despite being Chinese. nCov is exposing Asian Americans to this dilemma, as well as an opportunity for more of us to find unity with Asians across generations and borders — something that’s needed more than ever in these trying times.

I have confidence we can find that sense of solidarity because I think that a situation like this exposes the fact that the attackers don’t care about how assimilated we are at all. At the forefront, there is a serious issue of Sinophobia erupting from the nCov crisis, but there is also the bleed-over of racism facing all Asians for the simple reason that racists can’t tell or don’t care what the differences are between any of us. The nCov crisis will serve as a useful reminder of this to Asian Americans.

One of the most difficult challenges very-assimilated Asian Americans will face is seeing their friends and coworkers and peers react to the deluge of coronavirus news. The paranoia and groupthink caused by the nCov news coverage will strip the masks of otherwise “liberal” and “progressive” individuals.

It’s a clear opportunity to re-evaluate who are our allies and who are just putting up a front. It puts in plain sight who are accepting our company only when it scores them points as cool, cultured people with a diverse group of friends.

It will also force Asian Americans to evaluate the bias the mainstream media has when reporting on Asian, and more specifically, Chinese issues. We should ask ourselves: Do other crises receive this level of hysteric coverage? Do they use language like “The Chinese virus” to describe other health crises? Where is their coverage of this season’s household influenza, which has already killed 10,000 Americans this year, where as nCov has killed none?

The nCov crisis is helping us get over ourselves and what we THINK are our issues

If you’re on Asian Twitter any day of the week, you’re constantly bombarded by the same discussions around topics like media representation and cultural appropriation. If you’re on more anonymous platforms, like Reddit, you might see a lot of hand wringing over hypersexualization, emasculation, and the battle over interracial dating. While these issues may matter at some surface and personal level for Asian Americans, it has been interesting to see how the nCov crisis has cut through all this surface noise and made more immediate the common threat of Sinophobia and racism towards Asians.

Microaggressions don’t have this same effect. They lead us to believe that racism against Asians is a minor inconvenience in the grand scheme of things. This jolt of explicit racism, unfortunately unavoidable, is at least a reminder of not just our true position in society, but the fact that we don’t live comfortable lives as the model minority. We have more to worry about regarding our relationships with white people than whether or not they’ll date us.

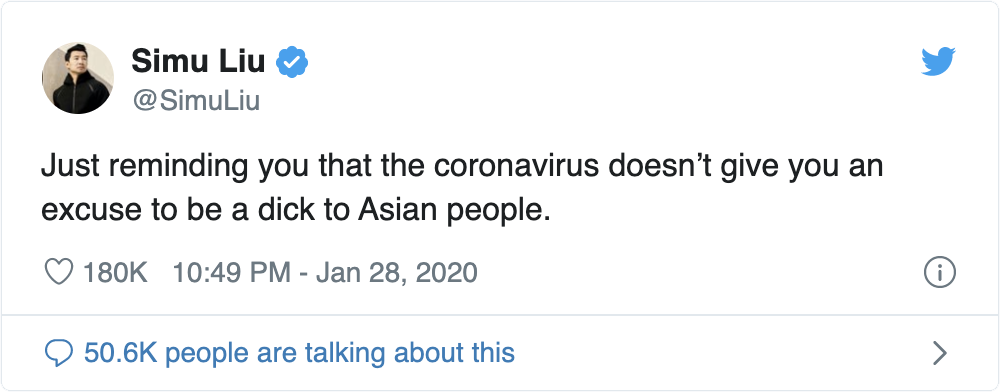

We’re even seeing Asian American celebrities, who normally have a reputation for being self-absorbed and focused on their own reputations, being galvanized in a unified direction. This includes Simu Liu, one of the first to call out nCov racism, broadcasting his message with a tone the Disney/Marvel PR department probably wouldn’t approve, on large, visible platforms like Instagram and Subtle Asian Traits.

Even Jeff Yang managed to write an op ed decrying the spike in racism, somehow without mentioning his son Hudson Yang, who stars in the hit ABC sitcom, Fresh Off The Boat, playing weeknights at 9pm Eastern/6pm Pacific, which you should really go see because it’s really good. The Twitter Blue Checks, with normally questionable takes, are actually rallying with and for us.

The nCov crisis is a real threat, but that threat can be elucidating

This is a rare and unique situation that Asian Americans have found ourselves in, because of the coronavirus outbreak. I’m not saying I’m happy about the very real possibility of violence, ridicule and discrimination that we are all being faced with right now. But I do think that being forced to confront it is going to exercise a muscle that Asian Americans don’t flex enough, which is to see clearly where the true threats are coming from, and to find solidarity with others like us in the midst of it all. The moment will be over shortly (let’s be real, China’s crisis management efforts has this shit on lock), and hopefully we’ll remember a thing or two after the dust settles about what it means to stand up for ourselves.

Comments powered by Talkyard.