In the ancient Indian epic the Ramayana, the old king Dasaratha sees omens that signal danger and baleful intent in the days leading up to the crowning of his noble son, Rama. The scene, like the rest of the Ramayana, was originally written in Sanskrit, but Ramesh Menon recounts it well in his English retelling: on the eve of the coronation, Dasaratha cautions Rama that “great fortune provokes great envy,” that “Man’s mind is […] capricious and full of treachery.”

These warnings are prescient. At length, conspirators hatch a plot to banish Rama and make his brother king, prompting Rama to embark on a spiritually and physically arduous journey. (Hence ayana, whose semantic field includes “journey” as well as “goal” and “direction”; Ramayana means the “Journey of Rama”). Personal trials and calamitous events ensue. If this is reminiscent of a myriad range of tales — from the Edgar subplot in King Lear to the main thread in Sundiata — the reader will be forgiven for thinking so: these are universal themes.

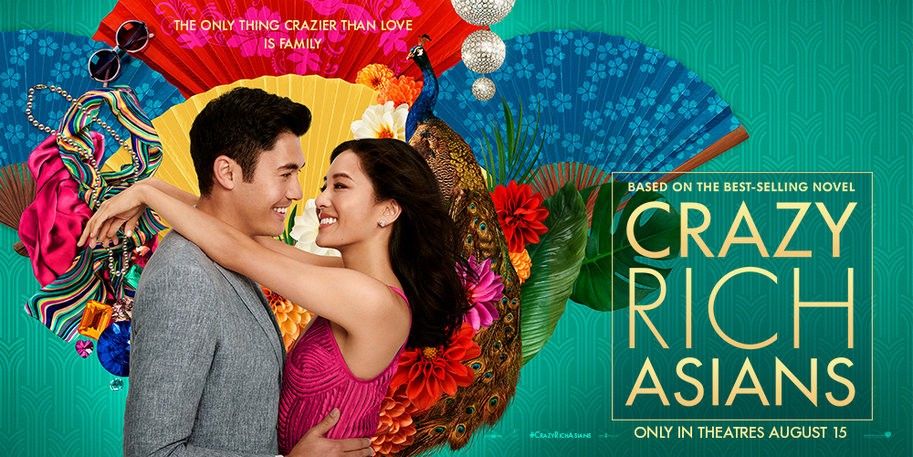

With the arrival of the landmark movie Crazy Rich Asians comes the reminder that great themes neither die nor disappear. They simply reappear, often veiled in new finery. In this case, they have reappeared amid sumptuous, decadent, and wildly entertaining scenes set in Singapore. They have emerged, most improbably, out of a Hollywood rom-com featuring an all-Asian ensemble and a mostly-Asian crew. Indeed, the movie constitutes yet another triumph in a banner year for minorities at the U.S. box office, one that began with the rousing success of Black Panther and one that, I hope, will continue as similar projects proliferate.

While Crazy Rich Asians is hardly Shakespearean, and while no characters plot to kill the illustrious scion of the story, we see human frailty — in the form of envy, resentment, and insecurity—rearing its perverse head at Rachel Chu, our protagonist, who undergoes her own journey amid her romance with a good man. Fortunately for the future of diversity and inclusion in these United States, that man happens to be Asian. Further, the trajectory of their romance brings viewers to a setting unfamiliar to the average U.S. filmgoer: Singapore.

Performed with restraint by Constance Wu, Rachel is a middle-class professor with average means. Partly because of this, she suffers the vicious attacks of women envious of her romance with Nick Young, the humble, shining prince of the Singaporean aristocracy, whose eyes emit warmth and kindness and elicit sympathy in spite of his family’s immense fortune. (Yes, dear reader; I, too, was won over.) As the narrative unfolds and enmity grows against her, Rachel proves to be a fighter with good friends. She radiates wit and grit: the essence of a hero who would earn our respect.

Nick, on the other hand, ably played by Henry Golding, carries his wealth in a manner that refuses to provoke great envy. Grace is his real nobility, and steadfastness is his charm. But Nick’s mother, Eleanor, opposes his romance with Rachel. From her vantage, the relationship competes with Nick’s obligation to return to Singapore to run the family business.

Clearly, the themes that distinguish his character arc seem hardly limited to the Asian experience, nor are they themes exclusive to the Asian elite. The Asian experience only provides the channels and conduits through which those themes may flow. Neither is Eleanor the ugly stereotype of the “tiger mother”; hers is a generation that prizes familial cohesion and obligation, which happens to collide with the independence cherished by her son’s

The conflict between choosing love and opting to satisfy the obligations of family is one as old as time, one that transcends space. It is there in Romeo and Juliet, there in the film Tanna, with its tale about the Ni-Vanuatu natives unfolding against the backdrop of the South Pacific. The trope resonates widely, from Bhutan to Bed-Stuy. This and the aforesaid facets are among the many that illustrate the broad appeal of Crazy Rich Asians, which seems, finally, to be for everyone.

Or almost everyone. Following the movie’s release, a few critics from well-meaning places denounced its lack of racial inclusion, or its “colorism.” While those claims are understandable, the world the script depicts is by nature an exclusionary world. To integrate, into its scenes, token minority characters solely aimed at diminishing its reputational liability would constitute cynical and dishonest storytelling, inducing an insult of a different variety.

It is true that the movie relegates brown-skinned Asians to guards at the gates of a mansion; it is true that it does not train the camera and microphone on any other Asians beyond the fair-skinned, ethnically Chinese. For my part, I would rather have seen a well-told and heartfelt movie about meagerly-paid Filipino workers in restaurants in Daly City than about elites in Singapore.

Yet here the ideal should not be the enemy of the good. Crazy Rich Asians is a good first step toward achieving Asian American “narrative plenitude,” a phenomenon originally discussed in Viet Thanh Nguyen’s book Nothing Ever Dies. (The concept would later be cited by Wu herself.) In this case, “narrative plenitude” is a scenario where stories featuring Asian characters appear in abundance. Upon reaching critical mass, the sheer glut of those stories would be such that cardboard characterizations of Asians possess diminished capacity to inflict harm, because they are crowded out by a host of genuine, heartfelt, and positive characterizations.

In other words, in a world where Asian Americans luxuriate in narrative plenitude, critics would less likely pillory this movie for its exclusion of brown-skinned Asians, because there would be so many other movies about brown-skinned Asians that such criticisms would no longer have merit.

The current Asian American experience is one of widespread narrative scarcity. The problem is systemic. So wanting to claim a small handful of roles for underrepresented minorities is to be expected: such roles are rarer than diamonds. Acknowledging the problem, Wu averred, “I feel for the people who keep hearing that this is the movement for Asian Americans and feel left behind, because there isn’t even a reference to somebody who looks or feels like them.” Reinforcing her rhetoric, Wu reportedly asked her publicist to insist, as much as possible, on booking female Asian American interviewers, so that she could help to create opportunities for them.

Notwithstanding the movie’s exclusionary milieu, it seems to be part of a broader movement that offers hope to all Asian Americans, even if it appears to start, as so many movements do, with the elite: those brokers of cash and credit, of power and privilege. This is regrettable. But, as if on cue, Shakespeare offers us a reedy reminder: “Nothing will come of nothing….”

This movie, then, is something.

Amid the divisive rhetoric about race, so much of it contentious and so much of it based on tragic reality, Crazy Rich Asians pleads the case for narrative plenitude, a generosity of portrayals featuring a wide array of Asian minorities, through its exploration of universal themes and honest depictions of characters who seem likeable, steadfast, and intrepid. It succeeds for its human portrayal of Asians, who, it turns out, are capable of more than just acing tests, writing code, and fomenting the next Boxer Rebellion. They can resist conformity; they can love.

Ultimately there is no Lear-like tragedy here or grand, epic story akin to those in the Ramayana and Sundiata, but neither is the movie pretending to be anything greater than the groundbreaking rom-com it markets itself to be. It is a landmark effort; we must concede that. It is heartfelt and funny; it is historic.

As with Rama, so with all of us; the journey continues, its course open to recalibration. There are omens ahead, understandable objections about the continued lack of representation, even in such a flick (it’s just a rom-com, for crying out loud!). The truth is that narrative plenitude requires stories, which require storytellers: more writers like Ramesh Menon, Viet Thanh Nguyen, and the author of Crazy Rich Asians, Kevin Kwan, to shed light on the virtues, frailties, and dramatic tensions involving Asian peoples across the world. Not without obligation, these writers ought to humanize Asians in view of those who might otherwise only see caricatures. A moment, then, for this benediction: let more narratives underscoring the vastness of Asia find release.

Comments powered by Talkyard.