December 2019 seems like such a long time ago. That’s when I decided to apply for a part-time temporary Census 2020 job as an enumerator. My goals were simple. I wanted to prepare myself for what we freelance writers call “the summer lull,” a time of the year when editors are less likely to answer emails or assign pitches because they’re on vacation and there’s less work. I also wanted to save some money so I could give my sister a small scholarship. She was admitted to Mississippi State University and our family’s plan is to fund my sibling’s education ourselves after my personal experiences with student loans.

I didn’t get a reply until March 10. At the time the coronavirus was already present in the state of Washington and had drastically affected China, Japan, South Korea, and neighboring countries. Italy and Spain’s cases were increasing, and COVID19 was just starting to get more attention in the United States.

After talking with my family, friends I met while backpacking who live in areas affected earlier, such as Hong Kong, Italy, and Spain, I decided I’d only accept the job if the Census supplied me with necessary PPE (hand sanitizer or spray, masks, and other low-cost bare minimum supplies), or if they offer a work from home option that would allow me to practice the recommended social distancing.

In order to work for the U.S. Census, you must get a fingerprint at a local center and pass a background check. As days passed, I noticed that experts were already warning against going to gyms, concerts, bars and restaurants. I thought about what I’d do and decided to ask about precautionary measures. My family also agreed that a job as an enumerator would be too risky at the moment, even though they knew it would mean I may not be able to contribute to my sister’s education.

On March 16 I called my state Census office in Jackson, Mississippi and mentioned my concerns over the coronavirus. I could hear from the background noise that there were several people and it was some sort of call center. When I was told that they’re doing what they can, they also said that if I must make a visit, there’d be no way to do this without talking to strangers.

How am I supposed to know whether or not a complete stranger is adhering to social distancing? Most importantly, how are they to know if I’m adhering to CDC recommendations? With so many local factories, warehouses, and manufacturing businesses who insist on remaining open or who don’t have jobs that can be done at home, there’s no way to know whether or not a stranger is practicing social distancing. Sadly, workers around the country must choose between increased risk of coronavirus or losing their paycheck. As an enumerator, I’d have no choice but to assume these same risks..

I explained to the person on the line that I couldn’t take the job, but would be more than happy to be considered for the position once a vaccine was available or it was safe to go out.

On March 27 I got an email explaining that any field operations were actually suspended on March 18 and that the job would still be waiting for me once it was safe to go outside again.. The email was sent 11 days after this decision was made.I was relieved to see that the Census had made this decision, but I also felt a bit gaslit. I recalled that no one had any answers for me when I voiced my concerns a few days earlier. The Census has a lot of resources at its disposal: ads, social media accounts, and various communication tools. They really could have used the tools they have at their disposal to communicate their decisions with us and let the public know that enumerators wouldn’t be able to follow up with them.

The Trump Administration has constantly downplayed the threat of COVID19, but as a federal organization that relies on workers to visit the homes of strangers, they could have done their own independent research much earlier. I know that, like me, many applied to this job as a temporary source of extra income, and it would have been nice to have more time to plan for a job we could no longer do.

I’m still glad that the Census shut down any activities that may require visiting people at their homes, but I can also imagine that many prospective enumerators needed the job to assist with current economic needs. Since we never had a chance to start our jobs, we can’t apply for severance pay or additional benefits that would substitute what we would have earned on the job.

The U.S. Census is Struggling to Earn Public Trust

The Trump Administration has caused minorities, women, and immigrants to look at federal agencies with an eye of mistrust. I’m sure that many federal employees likely don’t share his political stances, and entities such as the U.S. Census aren’t meant to be political in nature.

Federal law requires the Census not to share identifying information with other federal or state agencies, meaning that undocumented immigrants and other vulnerable persons don’t have to fear participating in the Census, but that doesn’t mean the Trump Administration won’t try to weaponize the Census for his own political gains.

It’s important to look at the history of the Census to better understand why minorities and other marginalized groups don’t trust it. The constitution requires a Census count, but it allows Congress to determine how it will enumerate, or count, individuals across the country.

You’ve probably seen Census ads that mention how important it is to send your responses because it allows government entities to have data they need to fund projects and organizations, such as libraries, schools, infrastructure, health clinics, and even transportation. A lot rides on a small set of questions that asks people to self-identify their race, discuss their wages, and let a government agency know how many people live in their home. The U.S. Census is used to move money, and this in itself is inherently political.

Data from the Census is also used to ensure that the House of Representatives reflects the country’s population at a district level. The number of representatives in a state fluctuates with population changes. Members of the House of Representatives represent certain districts, and states are allowed to redraw these as they see fit. This has allowed states to practice gerrymandering, or redrawing districts in ways that make it easier for certain political parties to win elections. In short, this “apolitical” data is actually used to make some very important decisions that affect how marginalized peoples relate to power and even influences who we can vote for depending on our address.

Miscounting POC, Stirring Fear in the Undocumented Community

In 2019, there was speculation on whether or not the Census would ask a question about immigration status. The Trump Administration has been adamant about making life as difficult as possible for undocumented immigrants and non-US citizens. Originally, he wanted the Census to include a citizenship question to get an accurate number of non-citizens in the United States. After theatrics about the matter, the Census will not move forward with this, much to the relief of immigrants’ rights advocates across the country..

Of course, the Supreme Court had to step in and block Trump’s proposed citizenship question. Trump then signed an executive order demanding that federal agencies turn over as much information as possible on non-citizens currently in the country. Per the executive order signed on July 2019, all agencies must provide this information to the Department of Commerce.

Another major change was that couples are now able to answer whether or not they are same-sex or opposite-sex, and whether they’re married or not.

Again, the lack of questions about citizenship, and the ability for LGBT couples to self-identify are huge wins, but there has been a lot of flip-flopping . These wins don’t guarantee an accurate count of minorities. The Census is known for consistently undercounting the Black community. Up to 9% of Black people weren’t counted across the country, which means there were fewer funds that were allocated to their needs.

The Census, as well as nonprofits vested in its success, did a good job of making sure the Latinx community was aware that there would be no citizenship question, but there was little outreach to undocumented Black or Asian-American communities. Up to 1.3 million of undocumented people are Asian-American, and an estimated 3.8 million undocumented Black people live in the United States. In the coming months, we’ll get a clearer picture about whether or not the Census made these communities feel safe enough to send in their answers. AAPI Data guesses that the Census probably didn’t.

Minority Groups and Disaggregated Data

By far, the most important win was the ability to have disaggregated data about ethnic groups. Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders have suffered disproportionately from the “model minority myth.” Though it’s true that several AAPI groups fare well in comparison to others, it’s important to get specific information about the many diverse Asian and Asian-American communities around the country.

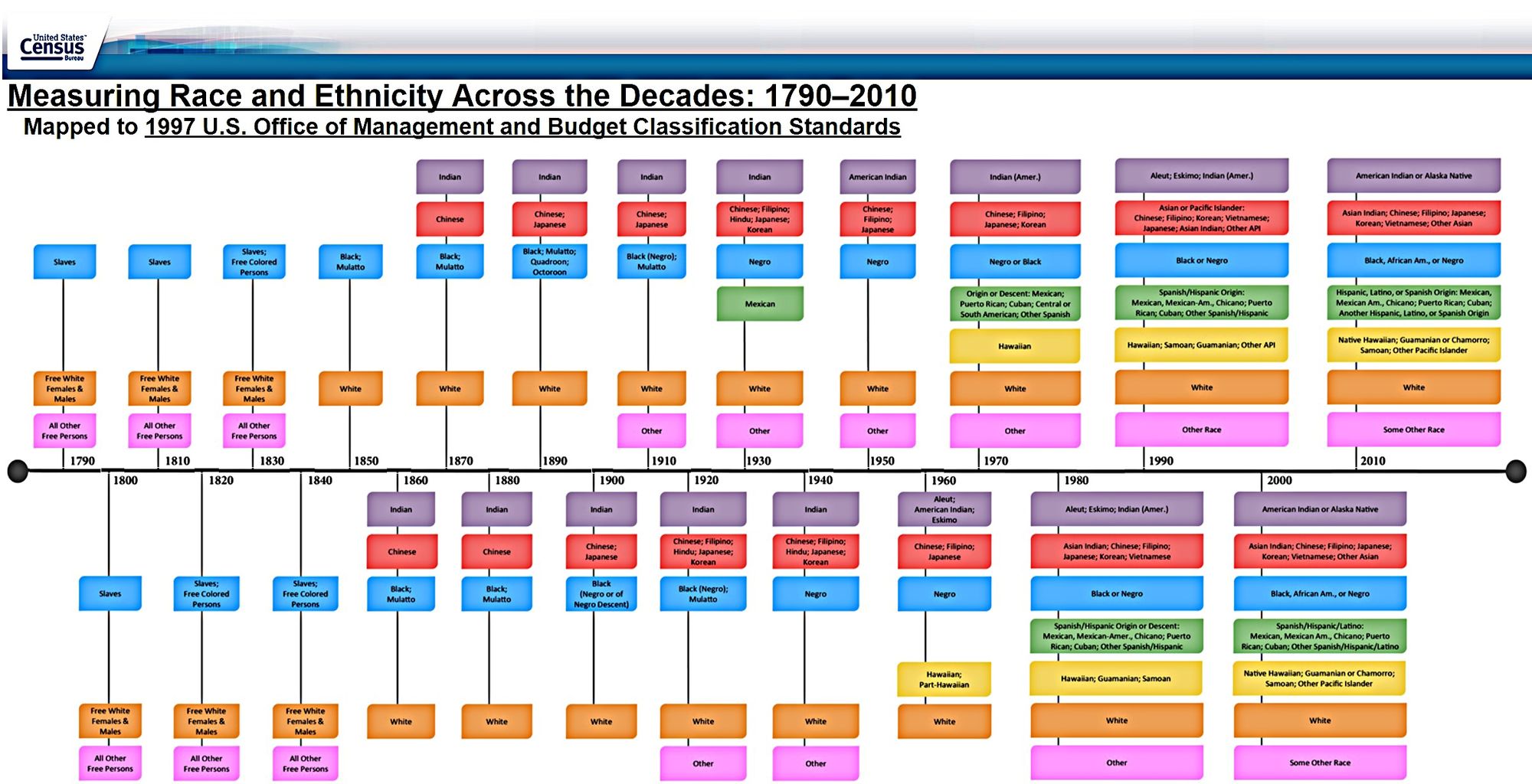

The Pew Research Center states that the Census has always asked about race, but major changes occurred in the 1960s that shifted the way people in the United States think about race. Anti-discrimination laws necessitated a new way to account for minorities gaining access to new work, education, and other opportunities. As voting laws changed, the Census had to make sure that they had data on minority voters so that they were included in the electoral process. Changes to Civil Rights, electoral law, and other policies affected the Census and forced the agency to gather data on Americans using these changing standards. We can expect future changes in thinking to affect the way the Census is conducted in the years to come.

That’s because the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) sets the standards the Census uses to collect its data. The OMB changed its practices in 1980, 1990, and 2010 after reviewing comments and suggestions to ensure that data-collection was as accurate as possible, and after a review of current practices on data collection.

Experts still lump Asian-Americans into one group based on their race instead of using data to understand the diverse circumstances within Asian-American communities. While the percentage of certain Asian-Americans in poverty may be lower when looking at data as a whole, class differences exist for any racial or ethnic group, and even disaggregated data misses these distinctions.

It is through more specific data sets that we know 27.4% of Hmong residents of the United States live in poverty, while up to 75% of Taiwanese-Americans have a Bachelor’s degree. In fact, Asian Americans Advancing Justice says that people didn’t have the choice of self-identifying on their own until 1960. A census enumerator had to watch them, and usually affected how minorities identified themselves when answering questions. There’s no question that racism and bias had an effect on past results and answers.

The 2020 Census form includes a separate question for people who are Hispanic, Latino or of Spanish origin. This allows people to write in their nationality if they are neither Cuban, Puerto Rican, or Mexican. Since people who are lumped together as Hispanic or Latino can be of one or more races, they must also answer the next question, which asks if they are white, Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, or if they identify with more than one race.

Despite ensuring that data can be disaggregated according to race, ethnicity, or national origin, the Census hasn’t allowed us to make sense of other truths that can be missed unless we look at class and socioeconomic status. Asian-Americans are the most economically disadvantaged in New York City, with up to 25% in living in poverty. These poverty levels continued to exist even for people who obtained high levels of education. Think tanks such as the Pew Research Center often use qualifiers to denote that Asians are less likely to live in poverty than other racial or ethnic groups in the U.S., and this completely erases the plight of Asian-Americans in poverty at all levels.

It’s true that the U.S. Census has no control over how their data is used, but increased outreach in languages other than English or in ways that are culturally relevant could increase participation and allow the many diverse Asian-American communities across the country to voice their needs. On February 2020, the Chicago Tribune reported that up to 66% of Asian-Americans were born outside of the U.S. Clearly the model minority myth isn’t just hurting how people perceive new immigrants’ socioeconomic status. It’s clear that more needs to be done to reach people who might not feel comfortable filling out forms in the English language, or helping those who are simply unfamiliar with something like the Census.

Where We Were, Where We Are Today

I don’t know when the U.S. Census suddenly began taking COVID19 seriously, but I’m glad they did. I have no doubts that other potential employees voiced concerns, as did public health experts across the country. CNN first reported about possible PPE shortages on February 2020, and these fears have materialized. It’s difficult to find proper surgical masks, disinfecting wipes, rubbing alcohol, or hand sanitizer. Panic shopping has caused some people to hoard items before others have a chance to purchase them. Had the U.S. Census purchased some of these items for us, it would have meant we’d have to use PPE that could go to healthcare workers, grocery store employees, and others on the front lines of this crisis. Shutting down these operations was the right call in light of these circumstances.

As it pertains to race and ethnicity, the validity of the Census’ questions on race have been questioned and criticized to no end, and for good reason. Race became an important category in the Census in the 1900s, when it was okay to openly support eugenics. Ironically, it’s important to count race, gender, and other factors in order to help marginalized communities, but the roots of collecting this data are dark.

The U.S. Census also needs to consider other aspects of race in the midst of the pandemic. The 2020 Census is the first in history to offer an online option. This is convenient for people with wifi access, but studies show that only 75% of people in the United States have access to wifi, and 90% of adults use wifi. Whites have more access to wifi they can use at home, and roughly 10% of Americans don’t have access to the internet.

Enumerators are meant to reach out to those who may not have been able to complete the Census over the phone, or online. In Mississippi, where I live, Black people in the Mississippi Delta are the least likely to have access to dependable wifi. Going to their homes without proper personal protective equipment would put them at risk of contracting COVID19 if I unknowingly carry the virus. Considering the types of questions there are, it may not be possible to keep the recommended 6 feet (2 meter) distance required to keep locals safe, and the reality is that the Census should help enumerators by providing us with masks we can give people we may need to talk to, as well as other items we can use for ourselves so that responders are comfortable.

The Census as many of us know it today is an improvement over what it was before the 1950s, but that doesn’t erase the Census’ history of dismissing the importance of gathering data on marginalized communities. The COVID19 pandemic changed the way many industries and government entities serve their communities, but that doesn’t mean that federal agencies and programs shouldn’t center vulnerable groups into their decision-making. The U.S. Census should consider available solutions to ensure that marginalized people feel comfortable participating in 2020 and subsequent years.

- Improve language access and culturally relevant outreach. People can fill out the Census in many languages, but outreach is highest for the Latinx/Spanish-speaking community. Building on these models to identify areas of need in the many Asian communities can help improve the relationship between the U.S. Census and Asian-Americans. It’s not enough to have forms in a language people can understand. Organizations like the Census need to ensure its efforts take a group’s culture(s) into consideration to maximize participation and reiterate that their responses are safe.

- Work with trusted community-based organizations that invest in education, empowerment, and equity. There are many organizations that work with marginalized communities and are heavily invested in making sure the communities they represent feel more comfortable engaging in work that affects policy. Some examples are Asian Americans Advancing Justice, Partnership with Native Americans, NAACP, or the National Center for Transgender Equality, to name a few. Some of these have partnerships with even smaller organizations across the country.

- Fund initiatives that work with minorities in rural areas. I live in Mississippi and have friends all over the Deep South. Language equity, cultural outreach programs, and other services for immigrant and Native American communities are lacking. Nonprofits that service Black residents operate on shoestring budgets, yet as people of color we face many similarities and suspicions when it comes to our relationship with state and federal government entities. There’s not enough data to gage whether or not enough immigrants participate in the Census in these areas, and that shows that the relationship between the Census and communities of color in rural parts of the country needs some work.

- Increase transparency and accept suggestions from people directly affected by the process. This may mean getting feedback from enumerators, sponsoring a study about methods that work, and incorporating suggestions of people who still fear that Census information may be used against them.

- Improve relationships with public health experts. COVID19 isn’t the only pandemic the U.S. has ever dealt with. It’s important that organizations relying on person-to-person contact can educate future employees on how to stay safe, commit to providing PPE without compromising healthcare workers, or find ways to modernize the Census while being inclusive of people who have limited to no access to the internet or phones.

During times like ours, it’s important that the Census embraces its history and makes amends for how its lack of proper data collection has harmed communities of color as well as other vulnerable populations. Throughout history, Census employees were allowed to force communities of color to identify in ways that are convenient for white people.

It took years of advocacy, comments, and organizing just to get a few extra checkboxes that can help our people answer questions in a way that serves them. I still don’t blame people of color, the LGBT+ community, and undocumented people for not trusting the U.S. Census, even as it provides much-needed temporary work for many employees across the country. While the Census is important in ensuring that communities have the funds and resources they need, it can also be true that people with a history of experiencing oppression won’t feel compelled to have government entities until they can reassure the public of their transparency.

Comments powered by Talkyard.